|

|

|

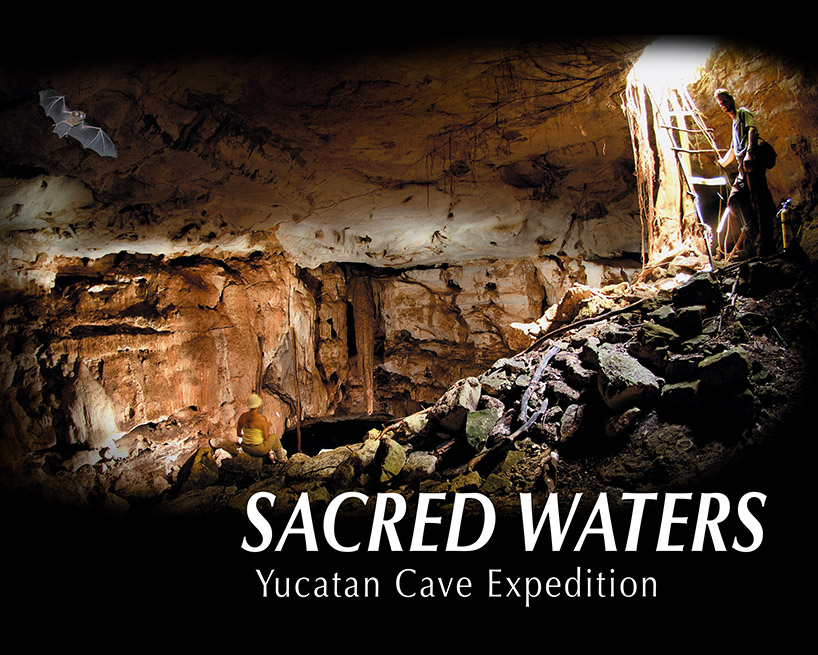

“A true cave explorer crawls through a lifetime of slime and bat guano in hopes of finding just one great passage.” The search continues!

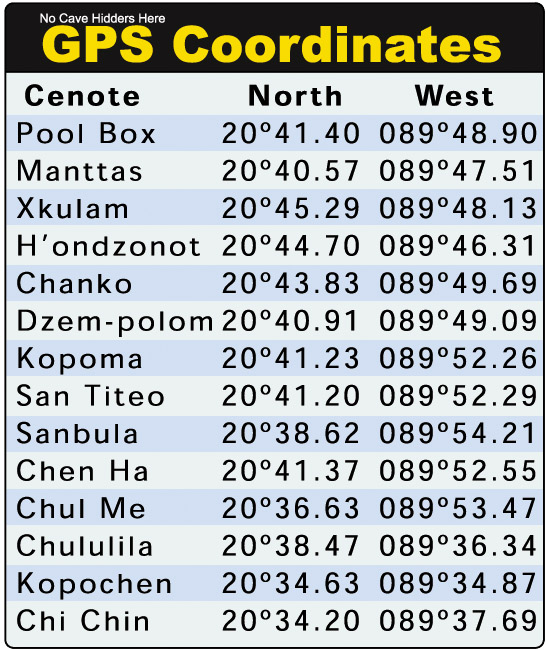

Returning to Mexico’s Yucatan and the “Ring of Cenotes” for another attempt of discovery was our goal. A team of six eager explorers packed climbing equipment, side mount gear, a crate of mosquito spray, and high hopes that a new, unexplored area might reveal undiscovered passage and a great archeological find.

God created the beautiful labyrinth of submerged passages, but sometimes I feel he forgot the Yucatan’s surface. Rough limestone rock, little topsoil, and the beating heat from the sun are only some of the tortures the surface of the Yucatan can throw at you The plants themselves hate intruders; almost every living plant has developed some type of thorn, poison, or sting. I rubbed my leg against something that must have been called the Blow Torch plant as it felt as if my leg was on fire. But plants cannot chase you down like the insects that must feel as though they have been placed into purgatory, and the only way to escape their fate is to drive all living animals insane. Drenched in the strongest mosquito spray was our only futile defense against the multitude of horse flies, bands of bloodthirsty mosquitoes, and angered bees. |

|

| |

|

Above: Cave explorer Dave Miner stands in front of one of the many insect infested cenotes we discovered in the Yucatan scrub jungle.

Below: Disturbed by our bright cave lights, a small group of bats cling to the cave ceiling. |

|

|

|

| |

Logistics for such expeditions into the remote villages of the Yucatan can be very difficult and without the proper local connections, impossible. For several years, I have returned to the Yucatan along with a small band of explorers. Over the years, I have become friends and colleagues with many of the local divers and government agencies. The Ecology Department provides our team with the required government paperwork, clearing us for exploration in the Yucatan along with requests for local village authorities to assist in our efforts with guides, sherpas, and lodging assistance. Aquatech - Villa DeRosa provides our team with a large van, a one-ton flat bed truck, and 30 aluminum, 80 cubic foot cylinders. An eight CFM compressor is provided by Protec Dive Center in Playa del Carmen.

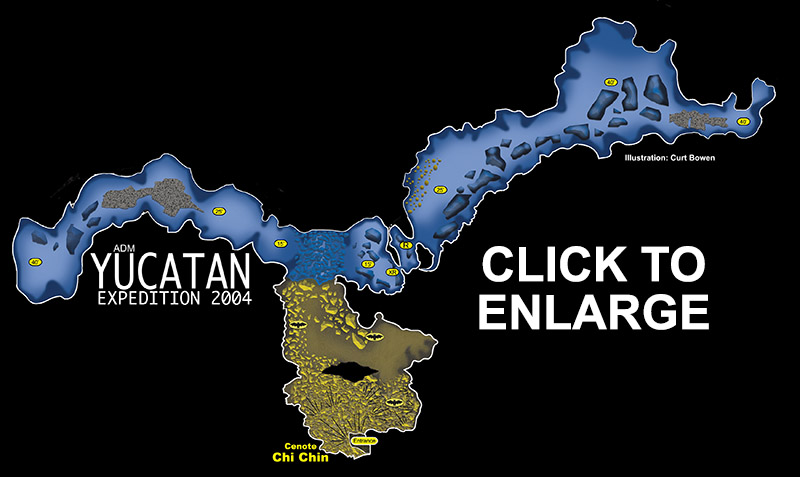

Yucatan 2004 expedition took place in the small village of Chochola, which is located 90 kilometers to the south west of Merida, the Yucatan’s state capital. We had selected this location because of its most western proximity and the lack of exploration in the past. Our goal was to explore, take notes, and document how the caves in this area compared to prior expeditions further to the east. Chochola’s female President welcomed our team with open arms and graciously provided a small two-room blockhouse that actually had a toilet and shower that worked…sometimes. She also provided a guide, sherpa, and guard from the police department to assist with locating and gaining access to the cenotes. |

|

| |

|

Above: Cave explorer Steven Serras peaks into a shallow hole a local farmer guided the team to on his property. Cenote Xkulam

Below: Brett Hemphill lowers James Kelderman onto a large jungle cenote. These large cenotes are often the homes of small stinging wasps. Cenote Kopochen |

|

|

|

| |

|

Above: Cenote Kopochen from waters surface looking upwards

Below: Explorer James Kelderman rappels into Cenote Kopochen in search of dry cave passage. |

| |

|

|

|

| |

After setting up base camp in the small house and hiring a cook for the week to follow, we set out to explore. I quickly noticed the terrain in the area was considerably rougher and overgrown compared to expeditions to the east. Travel down rough, narrow, rocky roads was very slow and the distances between cenotes was considerably long. This, along with the heat, bugs, and hacking our way through the underbrush quickly took its toll on the teams progress. But endeavor we did, and the list of newly discovered cenotes started piling up.

Further to the east, normal cenotes consisted of large diameter open pits with little to no going cave passage. Here in Chochola, the cenotes trend shifted to small cave entrances with larger underground chambers and small side mount passages. The karst itself appeared to be harder and possibly less soluble compared to the eastern limestone resulting in smaller passages and less cave formations.

After a couple of days of pounding the brush and making few satisfactory discoveries, the team chose to head further south towards the villages of Del Parque and Kopoma in hopes of discovering larger systems. |

|

| |

|

Above: A large lagoona invites the team for a swim out of the 99 degree heat. Cenote Chen Ha

Below: Brett Hemphill cools himself in the water as he signals to me that I am still number one. |

| |

|

|

|

| |

The Maya Indians have inhabited this area of the Yucatan for thousands of years. The Spanish discovered and converted the Maya to Catholicism in the 1600s, many times tearing down ancient Mayan temples to build their large churches. Like any culture, the Maya depended heavily on fresh water and built their communities around ample water sources. Almost every village I have visited in the past had the main church constructed within a stones throw of a main water source or cenote. Knowing this, I always search first for the village well or cenote.

Upon entering the village of Kopoma, I scanned the area around the town square and church for any type of natural opening, kept an eye pealed for quick darting cave swallows, and listened carefully for the distinct sound of the Moc Moc bird who always live in the cool and protected cracks of cenotes. But I heard and saw nothing. How could this be I thought to myself, no culture can build without water.

Stopping beside a small hot dog stand in the Town Square, our team set down for a bite to eat. A few local boys gazed upon us with faces of wonder and intrigue. As we ate our lunch, I pondered about the unusual absence of the water source when a thought came to mind. The boys who giggled and peered beside me have lived here their whole lives and probably played on every street and field within a few miles of town, and they would know the answer I seek. I asked my translator, Enrique, to question the boys about possible water sources in the village, such as open cenotes, caves, or town wells close to the local church. Of course a couple pesos were offered in an attempt to quicken their memories. Quickly, the boys jumped up and pointed towards the playground located beside the church. Eagerly following the children, they lead me into the playground and to a round concrete covered platform. The top of the platform had a square lid that had been sealed by concrete many years ago. This was it, a well, not more than 100 feet from the church that for some reason had been capped. But was it a dug well or an opening to a natural underground cave system? |

|

| |

|

Above: A small out of the place concrete structure with a strange square block on top pointed to the hidden cenote below the church. Cenote Kopoma

Below: Curt Bowen tends to the ropes as he lowers Tamara Thomsen into the small well shaft for cenote Kopoma. |

| |

|

|

|

| |

Our guide from Chochola quickly found a local official and to our luck a close friend of his and asked about the covered well. Excited, the local man quickly produced a pry bar and some digging tools and granted us permission to remove the cover. After a few minutes and some struggling, we managed to lift the heavy cover from the well and slide it to one side. A small man-made hole, no wider than your shoulder’s width, dropped deep into the ground. Peering wide-eyed into the well, we lowered a bright light on a string. Scurrying from the light, a large whip scorpion darted into a crack for cover as it passed. Thirty feet from the surface, the light dropped into a large cavern and landed in shallow blue water on the bottom.

Not particularly liking whip scorpions and being the broadest shoulder guy on the expedition, I quickly found Tamara Thomsen, the smallest and only female on the expedition and with a smiling face delegated this cenote exploration to her. As I anchored the lowering ropes, Tamara rigged herself with mask, fins, and a climbing harness.

Squeezing through the opening, I slowly lowered Tamara into the well shaft and past the nasty, hand-sized whip scorpion and into the knee-deep water. Tamara quickly reported a very large 300-foot diameter room with 15-foot ceilings. Dave Miner then suited up with his side mount equipment, and we lowered him and his gear into the well. After an hour of searching, we were disappointed to hear that no leads to off going tunnel were discovered. Pulling the two explorers from the well, we replaced the concrete lid and paid a local worker to seal the lid shut again. Several smaller discoveries were made in the Kopoma area but with very little going passage. |

|

| |

|

Above: The team moves base camp towards the east. Brett Hemphill covers his head in a futile attempt to protect him from the stinging insects. Obviously sacrificing his arms and legs for bait.

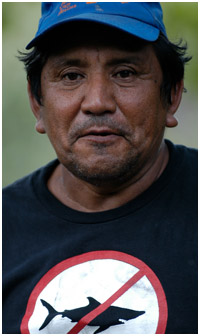

Below: Dionisio, a long time friend from the village of Mucuyche joins the team for the search of new cenotes. NO SHARKS |

|

|

|

| |

The team moved 20 kilometers to the east, just south of the village of Mucuche, an area where a previous discovery of the giant bottomless Cenote Sabak–Ha (ADM issue 3) from Andreas Matthes was made in 1999. We had stopped and picked up an old friend and local guide of Andreas’s to assist us in search of additional unexplored caves that can be easily accessed from a road.

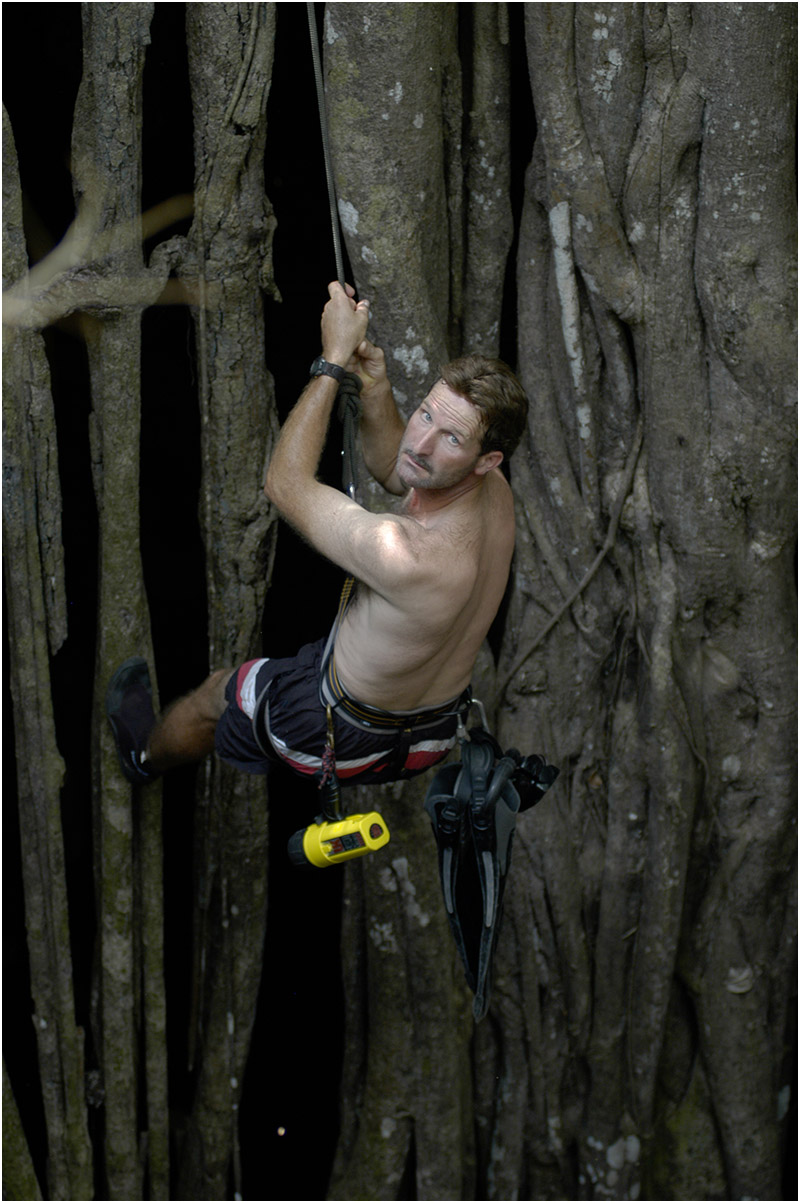

With only one day left for exploration, we wanted to visit as many systems as possible. But as in most plans, the translation of “easily accessed by road” was misinterpreted, and we found ourselves hacking tree branches and moving fallen timbers from a rock road just wide enough for the plants to scrap the paint from the sides of the vehicles. After several hours and multiple kilometers passed, we found ourselves half a kilometer from the desired destination, Cenote Chi Chin. All the translation was not lost, the half-kilometer trek through the thickets was easy, and the cave had a nice stick ladder descending the first 10 feet down.

The large dry cavern zone was split into two levels, a large upper room and a lower bedding plane below. Hundreds of brown and gray Mexican Fruit Bats franticly swirled around both levels, their daytime sleep interrupted by the new intruders into their cave. |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

At the far reaches of the dry cave, we discovered an inviting pool of clear water. Explorers Brett Hemphill and Dave Miner geared up with their Armadillo side mount rigs as the rest of the team shuffled cylinders down through the dry cave, over rocks covered in bat guano, and to the blue water sump.

Tying off the cave reel to a rock at the pools edge, the two slid beneath the surface and into the large tunnel towards the left wall. Twenty minutes later they returned with the news and survey data from their discovery. Recalculating thirds, the team searched the small room on the right and found a tight side mount restriction that lead into over 550 feet of large cave tunnel. This passage contained highly decorated cave formations; one large room, and several species of cave specimens were noted.

Overall the expedition went well even though we did not discover any extra ordinary systems or unique archeological discoveries.

But you can bet, the search continues!

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

| |

|

| Curt Bowen |

|

|

| James Kelderman |

|

|

| Tamara Thomsen |

|

|

| Steven Serras |

|

|

|

| Brett Hemphill |

|

|

| Dave Miner |

|

|

| Enrigue Soberanes |

|

|

| Dionisio |

|

|

|

| Pedro |

|

|

| Roger |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|