|

|

|

|

By Curt Bowen and Wes Skiles

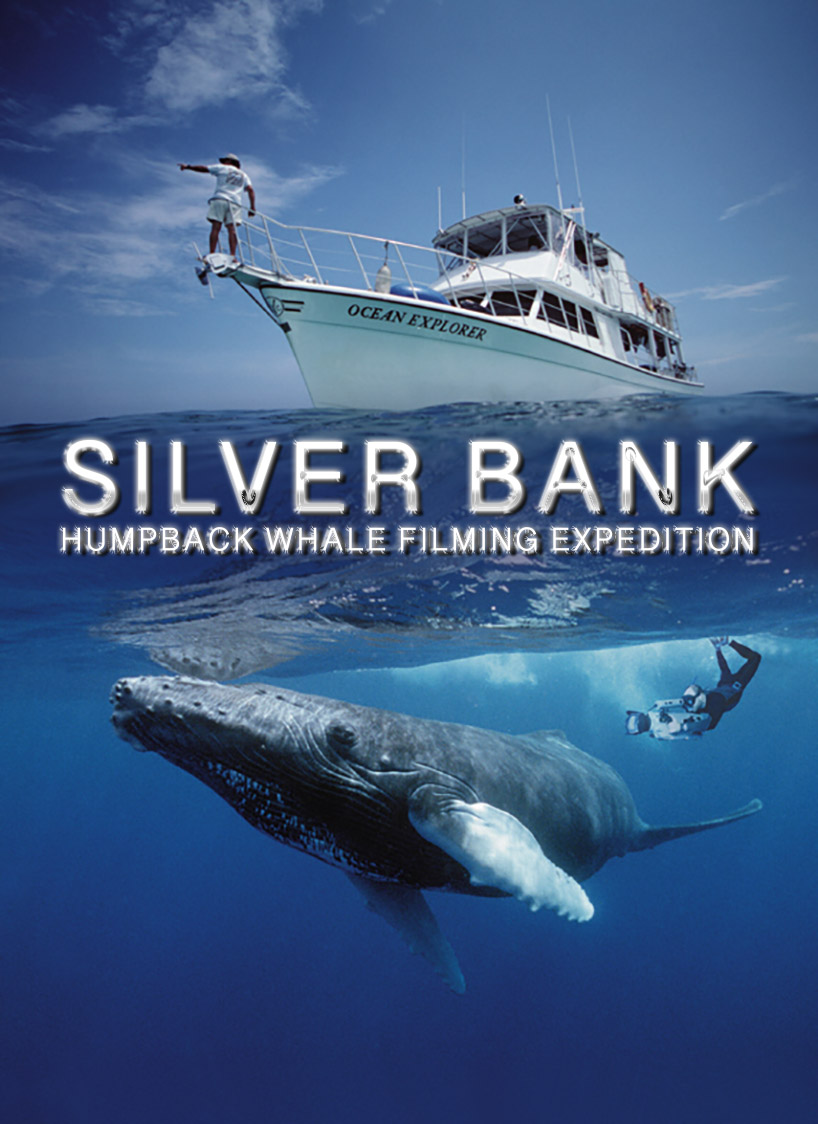

Slipping quietly into the water from the side of the rubber zodiac with my Nikon N90 in hand, locked in its quatica housing, I was ready for some shots of a lifetime. My ears sank below the water's surface and for the first time in my life, my head was filled with the musical rhythm of high-pitched wines and low grumbles of the whale song. The powerful vibrations seemed to penetrate into my inner core and become increasingly intense as I slowly drifted towards a giant, dark blue object suspended fifty feet almost directly below me.

Motionless, I patiently waited for the 50 foot, 35-ton mammal to finish its breathing cycle and surface for another breath. Temptation to dive down and snap a few quick photos of the sleeping animal was hard to overcome. However, according to the crew aboard the M/V Ocean Explorer, who for the past several years have conducted filming expeditions, the whale would quickly feel threatened and move away leaving my companions and I floating alone in open blue water.

|

|

| |

|

| |

A few small bubbles appeared from the whale's blowhole. It's head turned towards the surface. Like a submarine, the whale's bus-size body slowly rose towards me. I fired off twenty quick shots with my 18mm wide-angle lens, which makes the whale appear much farther away than it actually was. The wide-angle lens allowed my camera to get as much of the 50-foot animal into my frame as possible, while also making the water visibility appear clearer. Once the whale surfaced, I pulled my eye away from my camera's eyepiece and the realty of its immense size hit me. Caught up in the excitement of the moment, I found myself within arm's length of one of the largest mammals in the world. A few kicks of the whale's tail fin sent me reeling in a stream of turbulent bubbles as the whale moved away.

Surfacing, I cleared the seawater from my mask and realized that few can claim that they have been a few feet from one of these majestic creatures, let alone had his or her butt kicked by its powerful tail. Move over extreme sport fanatics, now that's an adrenaline rush!

The staff of ADM, Rusty Farst, Jim Rozzi, and I joined world renown underwater film producer Wes Skiles and Larry Curtis, underwater photographer of large mammals, for the first time ever high definition film production about the migration of the Humpback whales.

|

|

| |

|

| |

The setting was the Silver Banks, a large reef system located 85 miles north of the Dominican Republic. Every year, between the months of December to April, thousands of Humpbacks migrate from the northern waters of the Gulf of Maine, Canada, Iceland, and Greenland to the Silver Bank, to these warmer protected waters to procreate and give birth to their calves.

Almost brought to extinction by whaling ships during the early decades of the 1900's, an estimated 100,000 whales where killed. In 1966, the Humpback whale received protection from the International Whaling Commission. Since this date the Hump- back population has grown back to about 10,000 animals world wide, with the largest concentration of whales congregating in the Silver Banks every year.

|

|

| |

|

| |

Humpbacks are one of the most energetic whales. Known for their breaching, flipper slapping, and lobtailing, these impressive animals can provide a spectacular white water show and a lifetime shot for any photographer's portfolio. Easily identified by its knobby head and long white flippers, which can reach up to 16 feet long on large adults. The Humpback is propelled seemingly with ease from its extra large fluke (tail), which can produce enough power in just a few kicks to completely remove a 40 ton animal from the water for a spectacular breach.

Moving at speeds from 3-9 mph with short bursts to over 16 mph, the Humpback can travel great distances and for many days without rest. Adults must return to the surface every 15-22 minutes to breathe, while newborn calves must surface every 3-7 minutes. Because of this, Humpbacks became easy prey for whalers with sophisticated cannon harpoons and sonar tracking devices. |

|

| |

|

| |

Breeding occurs in later winter and early spring while they migrate towards or are in tropical waters. The gestation period is between 11 and 12 months. The calf is born tail first, weighing in at a whopping 2 1/2 tons and over 14 feet in length. The newborn instinctively swims to the surface for its first breath. Within 30 minutes, it can keep pace with its mother.

Like other whales, Humpbacks feed on plankton, schools of small fish and krill. During the period of time while the whales are in the Silver Banks, they do not eat. Only the calves suckle on its mother's fat rich milk.

Wes Skiles organized this filming expedition to test a new high-definition camera system. ADM interviewed Wes about this new technology and how it’s changing the quality of television.

|

|

| |

|

| |

Wes Skiles:

I got my first real taste of high-definition photography over three years ago when it was first introduced to professional photographers at the annual NAB conference in Las Vegas. At this conference they presented one short underwater clip taken in three feet of water somewhere out in the Pacific Northwest. That clip was all I had to see to know that high definition was going to be part of my future. I recall the image as so vivid and clear, I could practically sense the cold water coming through the screen. The details of the fish in the scene were so crisp and sharp that the illusion that one could actually reach out and touch it was compelling. Next was a shot of an eagle flying within a fjord, surrounded by awesome redwoods. Instinctually, I breathed deeply expecting to inhale the rich aroma of the trees and their surrounding elements. It seemed as though the scene was a magic portal that swept the vision from its surroundings. Only contact with monitor screen broke the spell that had quickly captured the visual imagination.

Upon my return to Florida I contacted my dear friend and equipment designer Val Ranetkins of Amphibico about the possibility of building housing for the Sony HDW series. It took a bit of arm-twisting and a second motion by George Lucas. Lucas confirmed my belief that this was much more than a new camera; it was a whole new way to experience the world. Shortly after this vote of confidence, Val began work on the housing for the first underwater high-definition system. I was thrilled by the prospect of moving into the new landscape of digital cinematography, but at the same time, nervous about the potential learning curve.

|

|

| |

|

| |

The new high-definition cameras are more like complex keyboardless computers fitted with a lens rather being viewed as video cameras. After twenty years of shooting film and video, it is an odd sensation to hear a hard drive spin close to your head while you are shooting. Unlike typical video cameras, HiDef systems have set- up cards that allow the user to write complex-color correction data to a disc. In turn, this allows the user to create "looks" for different scenarios. This is extremely useful underwater, where water filters out a majority of the most vibrant and brilliant colors of that world. Each diving situation may require a different set-up to realize optimum quality. A skilled and well-informed operator can correct all problems associated with blue, green, or gray water, multiple Kelvin light sources, caves, and deep water. Overriding automatic functions, one can make many additional corrections. This is extremely valuable to purists who like to make critical decisions about exposure and color balance. One of the greatest benefits of this system is its ability to "learn" about personal preferences and to store that information permanently in memory. Unlike most other video cameras, the HiDef camera is capable of morphing into a look and feel that best suits the user or client. Film lovers will also be impressed at just how close these cameras can come to making them believe it is film they are watching.

To join in on future whale, shark, dolphin, and blue hole expeditions contact M/V Ocean Explorer.

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|