|

|

|

|

| |

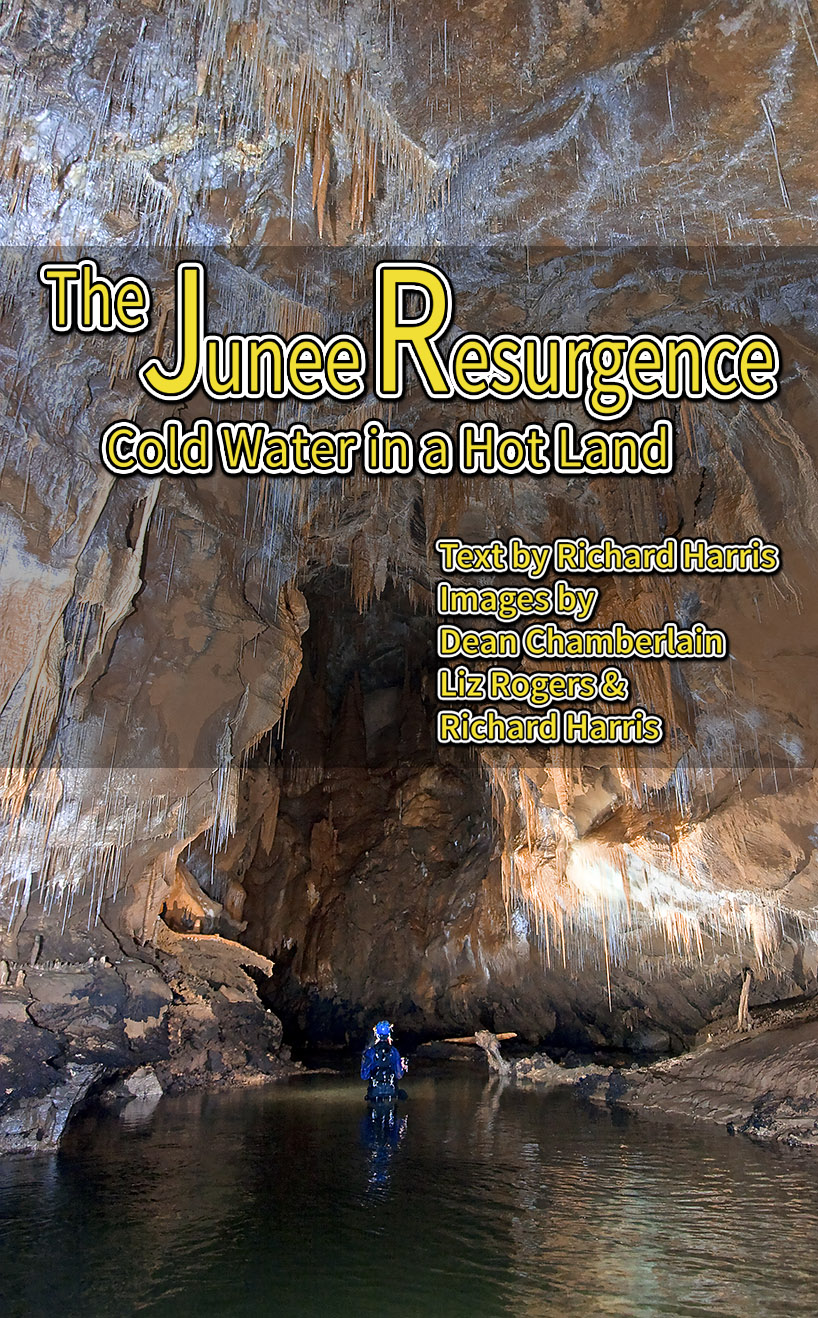

There’s snow on the peaks above and hail falling from the sky as the divers drag gear into the entrance of the flooding resurgence. The icy water has risen overnight as a result of heavy rains and threatens to repel the group from the entrance. They make heavy work of dragging SCUBA cylinders and caving packs up the rapids and the steam rises off their dry suits in the frigid air. And all this in the middle of an Australian summer!

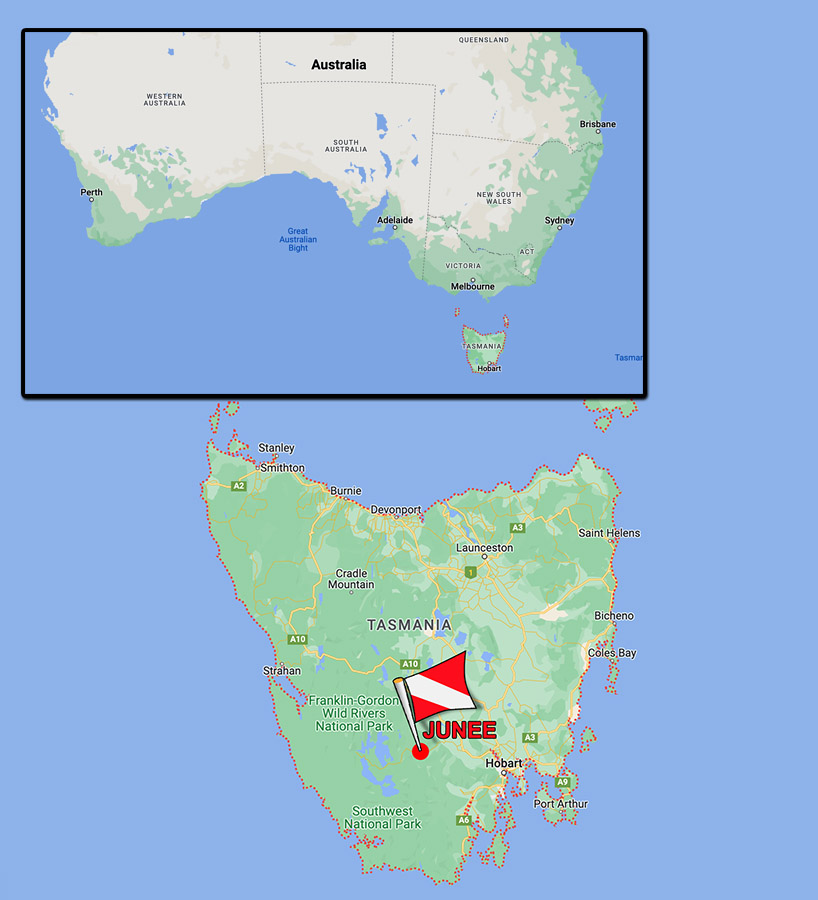

The group of cave divers from the Australian mainland have come to explore Junee Resurgence near the Mt Field National Park in southern Tasmania. There’s a saying in Tassie that goes “If you don’t like the weather here, wait 10 minutes!” The group have certainly experienced all 4 seasons in a day. Tasmania has a rich and diverse natural beauty including World Heritage Areas, inaccessible mountain ranges and stunning rainforests. It also contains several important karst areas like Mole Creek to the north, and the Junee-Florentine Karst to the south. Within these can be found Australia’s deepest vertical caves and multiple high flow resurging and siphoning stream-ways. Their names are nearly as beautiful as the sites themselves…Growling Swallett, Kubla Khan, Niggly Cave and Swallowing Gullet Sump hint at the raw nature of the caves.

|

|

| |

|

Top of Page: The true splendour of the dry chamber is shown in this beautiful image. Places like this certainly make the effort of traversing the first sump seem well worth while. Photo Dean Chamberlain

Above: The entrance to the Junee Resurgence can be seen from a public viewing platform. From this point the divers must wade upstream for over 100m to reach the start of the first sump. Photo Richard Harris

Below: Dean Chamberlain in the streamway, illuminates the delicate soda straws. Photo Liz Rogers |

|

|

|

|

| |

The difficult conditions and inaccessibility of the sites have meant they are less thoroughly explored than many of the mainland caves. Tasmania has a great tradition of dry caving but only a minority of the locals have taken an interest in diving the sumps or resurgences that have been discovered. Attempts at the flooded sections of Mole Creek caves were not made until 1974, and very quickly it became apparent that only the most hardy of explorers would make breakthroughs in the cold and dirty waters.

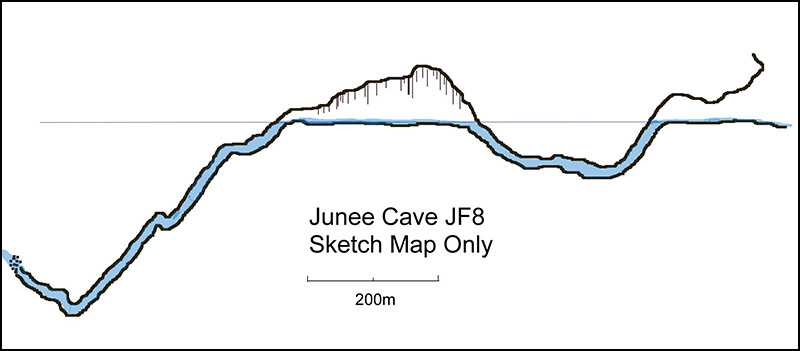

In 1973 a dye tracing study demonstrated a link between Growling Swallet (a siphon) and Junee Resurgence some 9km away; giving rise to the theoretical concept of the Junee Master Cave System. This attracted divers like Peter Stace, Ron Allum and Phil Prust to try their hand but high flow, complex passage and low visibility led to only 120m of underwater passage being found. Then in the early 80’s members of the Tasmanian Caverneers Club (TCC) made some further advances until finally Rolan Eberhard broke through into one of the most glorious stream-way chambers ever seen; “For Your Eyes Only”. This 250m long passage contains spectacular formations including thousands of beautiful straws.

To the dismay of the Tasmanians, the passage soon sumped again and this presented significant logistical problems at the time. Repetitive dive calculations, the heavy work required and extremely cold water made this kind of remote diving an unknown quantity. In addition, the second sump rapidly became much deeper than the relatively shallow first sump adding the complexity of decompression diving to the problem. Despite these challenges, the locals pushed the second sump to a depth of over 40m in 1992, but then some years passed until a group primarily involving Tim Payne and David Doolette from South Australia dived the cave to its current extent using mixed gas techniques. The sump reached a maximum depth of 62m and culminated in a rock collapse that appeared very difficult to pass.

|

|

| |

|

Above: Tasmania is an island state of Australia. It is located 240 kilometers (150 miles) to the south of the Australian mainland, separated from it by the Bass Strait, with the archipelago containing the southernmost point of the country. The state encompasses the main island of Tasmania, the 26th-largest island in the world, and the surrounding 1000 islands. Junee Cave general location is shown on the map.

Below: Liz Rogers preparing cylinders back at the accommodation in Maydena. |

|

|

|

|

| |

And so to the present and our group of 6 from Adelaide and Melbourne decided to try and reach the current end of Sump 2 and give a “second opinion” on whether it might be passed. We postulated that by using closed circuit rebreathers, we might have more time at the end to closely examine the breakdown area. 4 of us (the author, John Dalla-Zuanna (JDZ), Dean Chamberlain and Grant Pearce) would use rebreathers in the cave whilst the Liz Rogers and Jim Arundale would be on open circuit. We also hoped to video and photograph sections of the cave.

The unseasonably cold and wet January weather meant we were initially greeted by a flooded resurgence. In fact for Sydney cave diver Dave Apperley who coincidently happened to be at the site just ahead of us, the conditions became so bad that he was forced to leave his equipment in the site and beat a hasty retreat! We settled into a system of hauling gear through the first stream way (about 120m wading through rapids) and set up gear to dive the first sump. Day by day conditions improved and the water level dropped until the flow became quite manageable. The first sump is a somewhat intimidating dive at first. Visibility ranges from near zero to about 4m. Water temperature is just under 7 Celsius. Razor sharp limestone projections constantly threaten to tear a hole in your drysuit. The thick line has been laid to keep it away from the knife like projections and consequently often leads the diver into a “line trap” (a place where the line passes but a diver cannot follow). In the low viz this often means reversing and gently renegotiating the passage until you can “key-hole” through, often with rock scraping front and back. But on route you spy large cave adapted fish, almost white in the torch light. Small shrimps and what appear to be syncarids (another invertebrate) are also seen.

|

|

| |

|

Above: Photo In For your Eyes Only, looking back towards the first sump. Photo Dean Chamberlain

Below: Impressively long Soda Straws, pillars and many other varieties of speleothems formations can be found in the streamway passage. Photo Liz Rogers |

|

|

|

|

| |

The journey through the first sump is well worth it to appreciate the beauty of For Your Eyes Only. Although it is hard work hauling all the dive gear to the start of the second sump, frequent stops to marvel at the wondrous formations make the trip pass more quickly. Dave Apperley had managed to dive the day before we were ready to attack the second sump. He got close to the known end but was delayed by numerous breaks in the fixed line that required fixing. He also found the flow to be almost prohibitive…it didn’t bode well for our attempt.

It was decided that JDZ and the author would dive the second sump and a full day was spent by the group setting up the dive, placing all the open circuit bailout that would be required at the end of the dry chamber. On the day of the dive, the water level had dropped considerably which they hoped would make the passage through the sump much easier.

Setting off on their rebreathers, the second sump immediately looked different to the first. Larger passage with better visibility, the first section took them over silt mounds to a maximum depth of only 10m. Soon after, the passage started to descend rapidly. At 40m an area known as the “Teeth” forced them to duck under some large marble incisors on the ceiling. Continuing down to a maximum depth of 62m and a second minor restriction, they started to ascend until they reach the end of Apperley’s line repairs at about 58m. From here they laid some new 6mm heavy line to patch the final section leading to the breakdown area.

|

|

| |

|

Above: A sketch map by the author based on previous surveys by other divers.

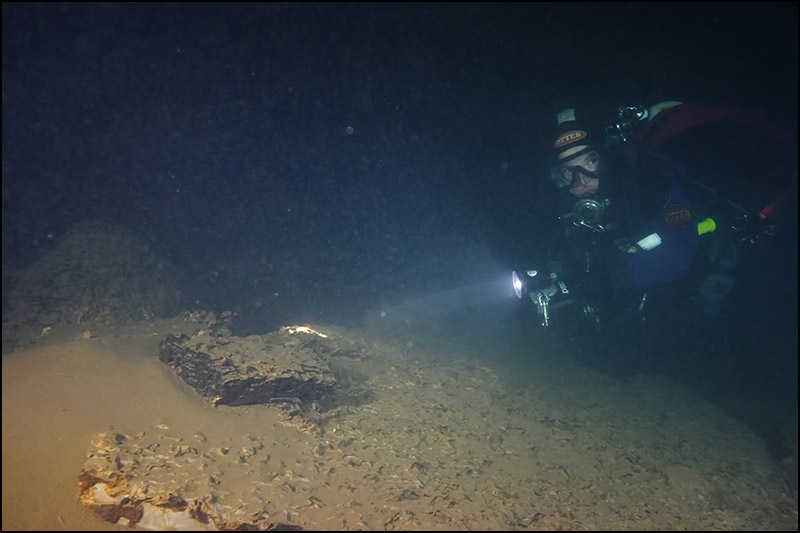

Below: Beautiful as the dry chambers are, the sumps in Junee are generally dirty and tight. Not well suited to photography! Here Liz makes her way through the first sump. Photo Dean Chamberlain |

|

|

|

|

| |

The rock pile ahead looked depressingly solid. Large boulders fitted together with tantalising cracks and holes just too small for a diver to pass; even perhaps with an “off-mount” rig. Despite studying the rockpile with care, they could not see anyway on. Still it was important to see for themselves and very satisfying to be only the 3rd and 4th divers to ever reach that part of the cave.

The trip out of a high flow cave is always easier than the brutal swim in! Decompressing in the flow can be a challenge to avoid being swept out, and the cold flowing water really strips the heat off you.

One further day to remove all our gear from the site and our visit to Junee was over. Perhaps some more resourceful divers will find a way through the obstruction at the end of sump 2, but for the moment the secrets of the Junee master Cave remain safe and sound.

References

Hume N. Cave Diving. In the TCC Exploration Journal Pp 31-50.

Payne T and Doolette D. JF-8 Junee Cave - Cave Diving Exploration Trip: March 2004. Speleo Spiel Issue 349, August 2005. |

|

| |

Below: L – R Richard Harris, Grant Pearce, Jim Arundale, Liz Rogers, Dean Chamberlain and John Dalla-Zuann. |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|