|

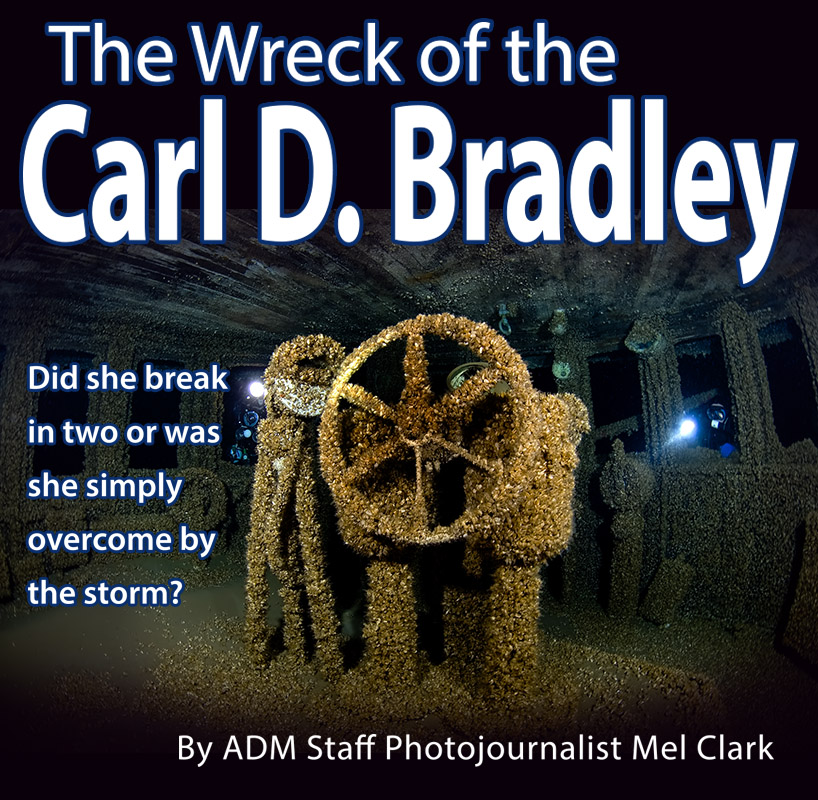

The Carl Bradley was the largest steel freighter on the great lakes in 1957 at a length of 639 feet. Ironically enough, the year she sank, 1958, was the same year the Edmund Fitzgerald (729 feet) was put into service and took the largest freighter of record from the Bradley. The Bradley was a self-loading bulk freighter. Her homeport was the small town of Rogers City where most of her 35-man crew was from. She was starting to show her age at 31 years and was to be laid up for extensive repairs. The ship owner, U.S. Steel, claimed the Bradley was still seaworthy and ordered one last voyage before she would be docked for 800,000 worth of repairs. This arrogance, coupled with Captain Roland Bryan who was known as a “heavy weather man”, sealed the great freighter and crews fate. At 530pm on November 18th 1958 near Beaver Island the Carl Bradley broke up and sank.

Watchman Frank Mays survived the shipwreck along with first mate Elmer Flemming. Mayes reported at 5:30 pm he heard a loud bang and looked back to see the stern swinging in the waves. The two managed to get into a life raft after being flung into the frigid waters. After spending almost 15hrs in a tossing and capsizing raft they were rescued by the Coast Guard. The life rafts of the day were just that, a raft, not the nice new age ocean going life vessels mariners have today.

Over the ensuing days only 18 bodies were recovered out of a crew of 35. To this day there are still 15 soles missing. After diving this wreck it is easy to imagine that some of these men may still be entombed in the wreck. In fact, this thought crossed my mind many times when we were on the wreck. How would I handle running into a dead body. I was lucky I never had to find the answer to this question during my exploration on the Bradley. |

|

| |

|

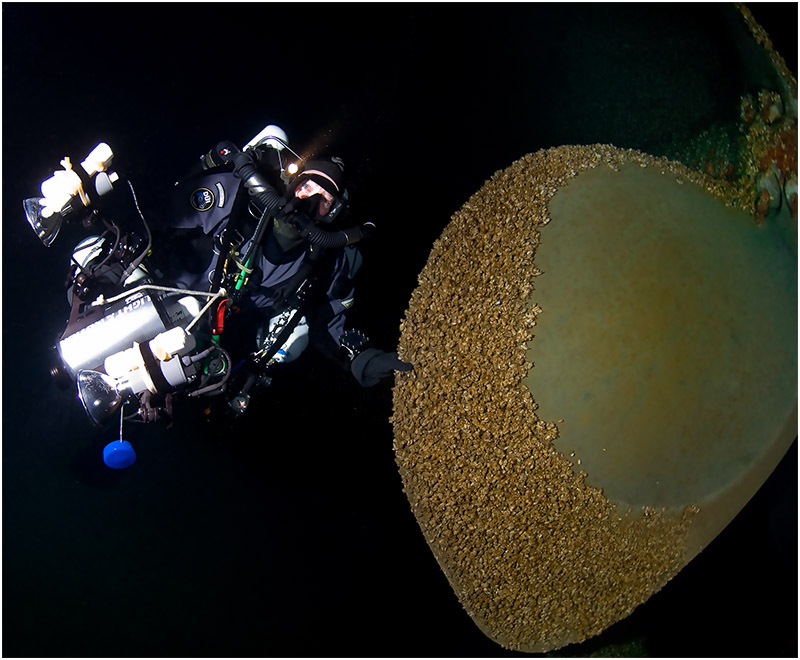

Above: Explorer and eagle eye Erik Foreman prepares for a scooter dive on the Carl D. Bradley in an attempt to prove once and for all how the wreck sank.

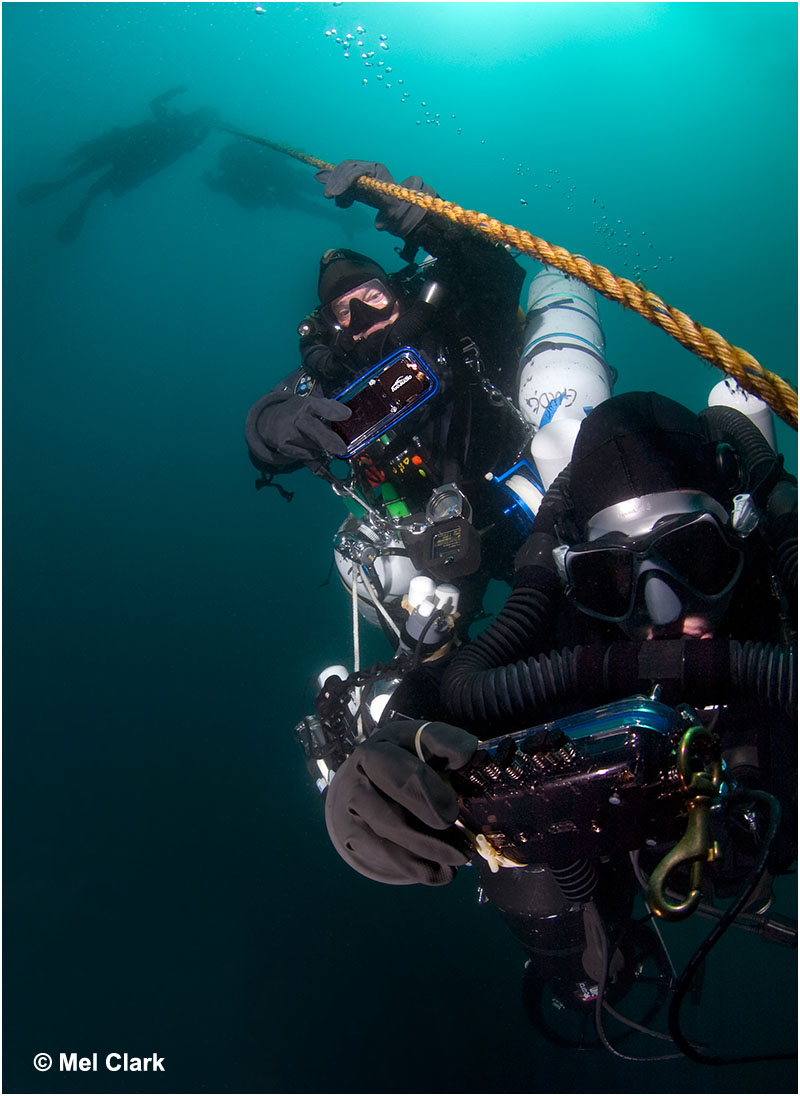

Below: Great Lakes wreck diver Ron Benson prepares as a safety diver for the first returning divers from the Bradley. |

|

|

|

|

| |

During the investigations after the sinking, the insurance company and ship owners claimed the ship was simply overcome by the storm and did not break up in an attempt to limit their liability. Other theories are the Carl Bradley had split in two due to her weakened structure on the surface and then sunk. This theory is supported by watchman Frank Mays eyewitness accounts of the sinking and has been the accepted theory for over 51 years. Some articles even say 90 feet of the bottom separate the two sections. Armed with this information, my CCR and a dive-x scooter I was ready to prove or disprove this theory.

The Carl Bradley offers many challenges for the Technical diver and this is what intrigued me to dive her. She is a very deep wreck sitting at 310 to 380 FFW and to top this off she is in Lake Michigan, which is not a tropical lake. The temperature at depth is around 39 F all the way up to about 60 FFW where the thermocline brings the temperature up to 58F. When you have over 4 hrs of decompression ahead of you the 60 FFW mark taunts you as you slowly claw your way up to it. When you finally arrive at 60 FFW it is almost like entering a warm bath. This warm feeling lasts for a while then the reality of the 58F temperature sets in and you realize that it is still going to be a long few hours. The other large challenge with diving the Carl Bradley is she lies 23 miles off shore resulting in a long ride out to her resting site. The great lakes are like inland oceans with a moody temperament. There is a reason the Carl Bradley and many other great freighters lye at the bottom, the lake can change from a glassy calm to an evil tempest in a matter of hours. It is not uncommon to start your dive on a beautiful morning and then spend hours riding a bucking decompression line. After you survive the decompression you now have to attempt to get back on the boat with an aluminum ladder that is clearing the water with each passing wave. Finally, to add insult to injuries, after getting on the boat you now have to spend hours fighting the weather as you return to port and hope to not become the next wreck on the lake. All of these challenges make the Carl Bradley a wreck for the hearty technical diver. But if you should manage to surmount all of these challenges the Carl Bradley is one of the best wrecks I have been on, she is simply magnificent and absolutely worth the risk and effort. |

|

| |

|

Above: With wreck depths exceeding 380 feet, divers endure the cold 39F lake temperatures and long four hour decompression schedules.

Below: Diver Erik Foreman lands on the upper wreckage at a depth of 340 feet. |

|

|

|

|

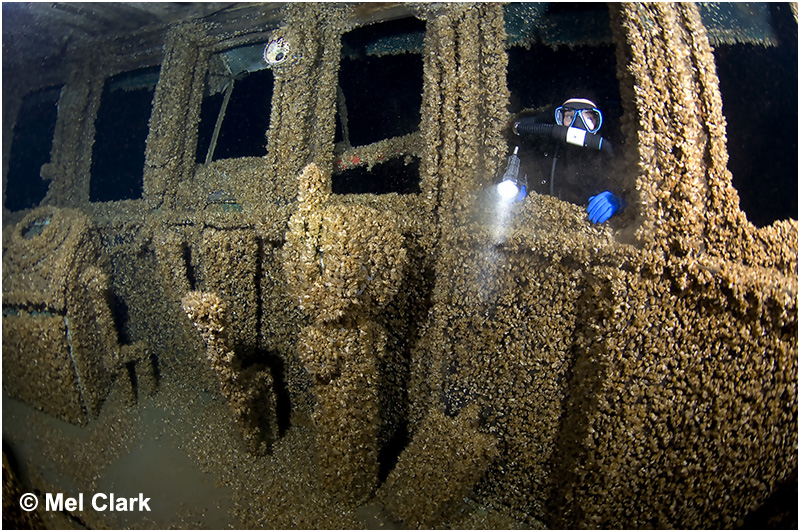

| |

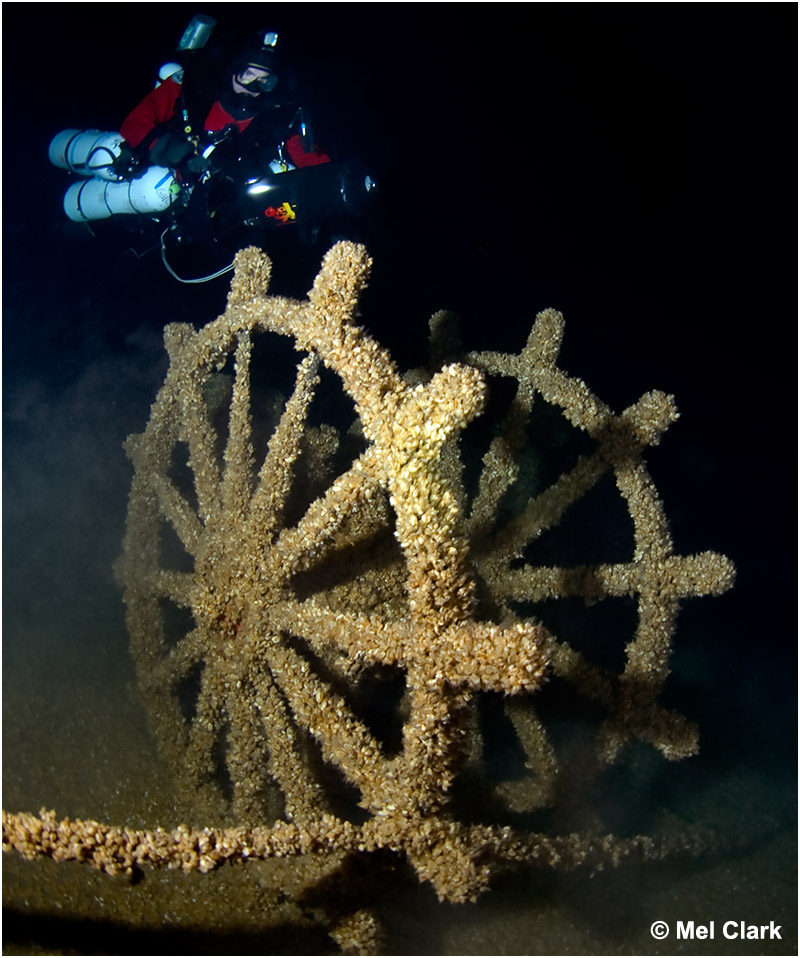

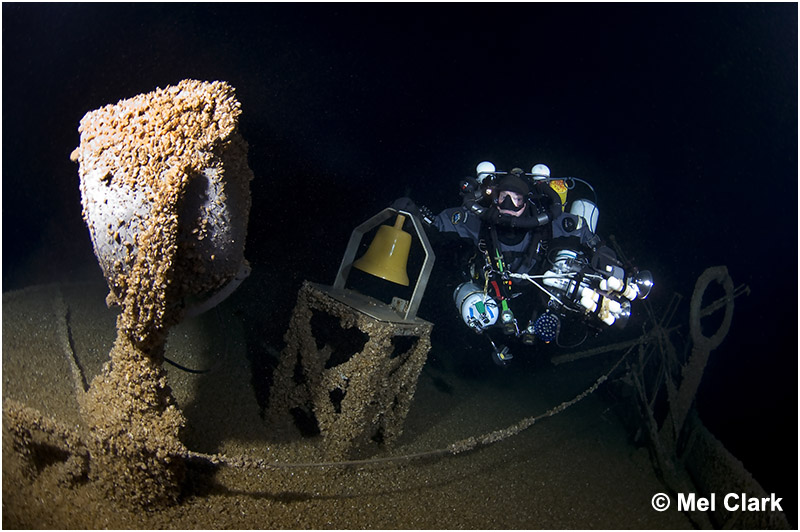

We met our boat Captains Jitka Hanakova, Ron Benson and first mate Lubo Valuch in Manistique Michigan and headed out to the wreck. Erik Foreman, Curt McNamee, Tom Kean and I would be the first team in. Captain Jitka and Ron would be our surface support and safety divers for today’s dive. The mooring line is attached to the port side superstructure behind the bridge and right before the loading crane. We stop to check the mooring line’s integrity before we started out to our targets. The first stop was the ships bell and spotlight. This wreck is now encrusted with zebra muscles. When diving the Carl Bradley keep this in mind as visibility for your pictures or video can be quickly destroyed by a poorly placed fin kick. The ships bell was removed in 2007 by divers and replaced by an honorary bell with the 33 sailors names that were lost that day. The new bell has no zebra mussels on it and looks a bit out of place. On top of the bridge along with the bell you will see a huge spotlight and a radio communication antenna. On each side of the bridge roof section is a wooden plaque with the ships name on it. The names use to be legible but are now completely obscured by zebra muscles. Under the name you can still make out the words pilothouse.

Since we are at an average depth of 340 FFW and my decompression obligation is exponentially rising I quickly make my way back to the ships loading crane. The crane and its rigging are still in place as if waiting to work on the next load. If you swim under the walkway you will see two huge spotlights with their lenses still in place on each side of the structure. Be careful when moving around this section, as there are a lot of loose cables and lines waiting to grab the unsuspecting diver. |

|

| |

|

Above: CCR divers Jitka Hanakova, (left) and Ron Benson (right) examine the new bell with the names of all 33 sailors who perished on the Carl D. Bradley that fateful day of November 18th 1958.

Below: On top of the bridge along with the bell you will see this huge spotlight and a radio communication antenna. |

|

|

|

|

| |

Our time on this dive is rapidly expiring, so Erik and I hit high gear on our scooters to get a quick glimpse of the bow. It is amazing to me how these huge ships can have such a narrow pointy bow. I get a shot of Erik at the bow and it looks like he is in a large rowboat not a 639-foot freighter! Erik and I head back to the upline with over three hours of decompression ahead of us. As I pass over the front superstructure I can’t help but notice all the portholes and wonder how nice they would look in my front room. Of course there is not time for such vandalism and it is not allowed either.

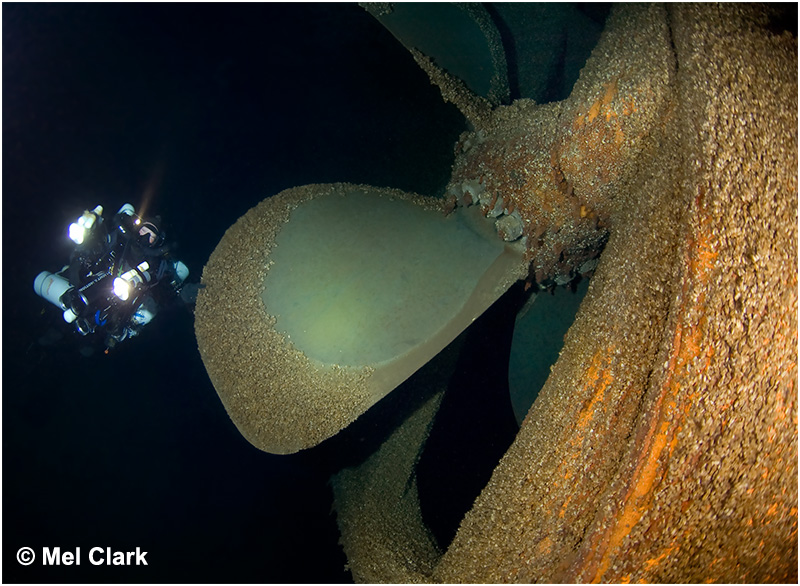

We were relatively lucky on this trip as the waters were mostly calm and we only were blown out one day. The next day we dived the stern. The mooring line had sunk over the winter so we had to grapple the wreck, or what we thought was the wreck. We descended down the line to a barren lake floor, determined not to be beaten we started a search for the wreck in 380 FFW. It was an amazing site after our 10 minute search to see the huge propeller and rudder towering over us. I must say the coolest effect was the shadow that the ship threw as we approached it. The stern section of the ship is suspended about 10 feet above the bottom. We would use this discovery on our next dive to prove or disprove the theory that she broke up on the surface and sunk. |

|

| |

|

Above: The extremely pointy end of the Bradley's bow makes it look like a small a small rowboat and not the 639-foot freighter. Diver Erik Foreman

Below Images: The huge propeller and rudder of the Carl D. Bradley loom out of the darkness at a depth of 380 feet in the bone numbing 39 degree lake water. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

After a quick look at the rudder and massive propeller we moved up the stern to explore the stern superstructure. Carl Bradley and her registered port of New York can still be seen on the stern. There is an absolutely stunning double wheel rear steerage station on the stern. Further forward of the wheel is the engine room vents and the rear ships mast. I would have loved to get a chance to go in the engine room but as we wasted over 10 minutes at 380 FFW trying to find the wreck we needed to get back to the upline fast. Erik and Tom took off on their scooters, Curt and I were left to swim. The irony here is we did not hook the wreck but we hooked the rear mooring line that had sunk. So now we were swimming and pulling along this line in a horizontal fashion for around 300 feet!! After we intersected our grapple hooked on the sunken mooring line and released the securing carbineer, we started our 4 hour ascent.

The weather gods were still shining on us for day three and we decided to do the bow section again. I wanted to get into the pilothouse and also to determine if the wreck was separated or not. I realized this was not a realistic single dive goal so we split the team in two. Ron, Jitka, Curt and I would get some more images of the bridge and superstructure. Erik and Tom would use their scooters and head to the break section. |

|

| |

|

Above and below: The inside of the Carl D. Bradley's pilothouse. |

|

|

|

|

| |

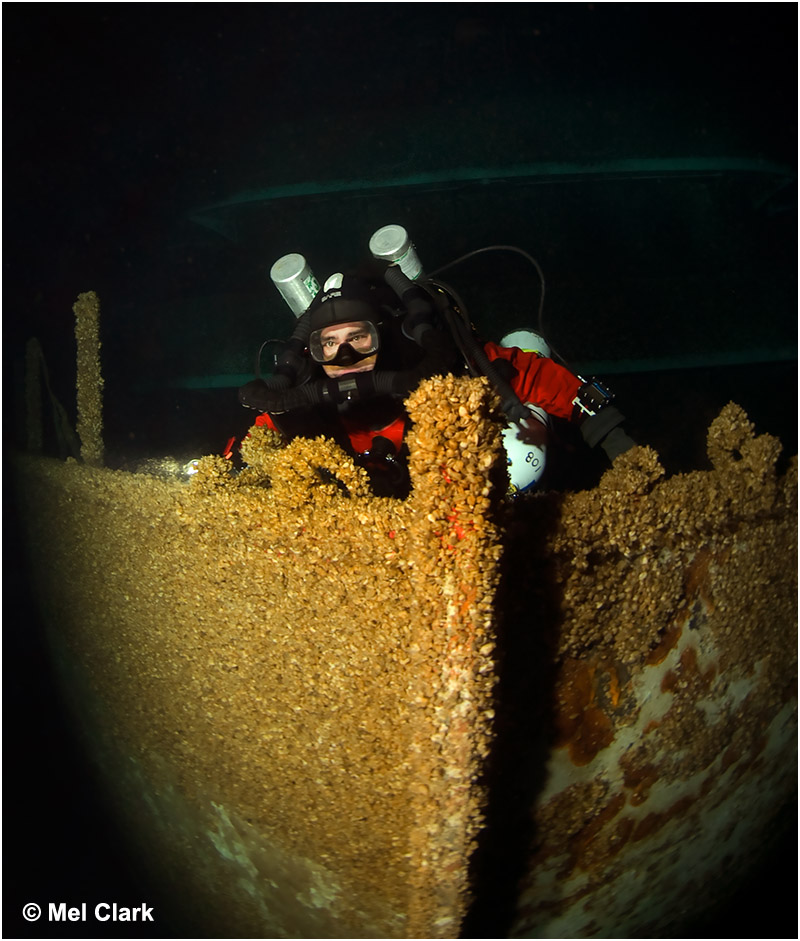

I was able to shimmy my way sideways into the pilot house. This was one of my most thrilling experiences mainly due to the fact that I was packed inside a tiny space at 310 FFW. I knew if I got stuck that my time and life would be in grave danger. Also I knew not many (if any) people had been inside this pilothouse since she sank and this added to my excitement, it’s great to be small at times. Everything was in place just as it was left that stormy night. I quickly moved around the circumference of the bridge imaging everything in sight.

Tom and Erik armed with their scooters headed aft towards the break. The mystery of the Carl Bradley sinking was finally solved. The ship definitely broke on the surface, but she did not split in two and sink. Instead, she split on the bottom of her keel and the two ends of the ship stayed attached by the top deck. This can be proven by the two sections being right next to each other on the bottom. If she did split in two on the surface, first thought is the two sections would not be in line and so close together on the bottom. This also explains why the stern is lifted at the back and not lying directly on the bottom. The ship broke on the surface and went down in a shape of a hinge on a door, with the center break section leading the way. When she hit the bottom the center break hit first and burred itself deep in the silt resulting in the stern section being held up at a slight angle. |

|

| |

|

Above and below: CCR diver Curt McNamee poses beside the new ships bell. |

|

|

|

|

| |

Frank Mays did see the stern flopping around in the rough seas that night, but the ship was still in one piece. The ship owners and insurance company were incorrect in saying the ship was simply overcome by the storm. The Carl Bradley had a weakened structure, which most likely resulted in the keel breaking. I am not an official shipwreck investigator; my conclusions are my own personal beliefs after exploring this shipwreck. This expedition was an exceptional experience. I would recommend this dive to anyone who has the necessary experience and is hardy enough to do it. Jitka of Shipwreck Explorers runs trips out to the Carl Bradley every year. Her rock solid seamanship skills will allow your dive team to enjoy this wreck with confidence. I want to thank Ron Benson for all his help and support to make this expedition happen. |

|

| |

|

Above: Divers line up on the decompression line awaiting the 3 to 4 hours to safely return to the surface. A small price to pay to visit a once in a lifetime shipwreck.

Below Images: Captain Jitka Hanakova removes her CCR equipment after returning to the warmth of the surface. |

|

|

|

|

| |

Below: CCR diver and Advanced Diver Magazine Photojournalist Mel Clark gives a thumbs up as the vessel returns to shore in Lake Michigan's rough seas. Another expedition completed! |

|

|

|