|

Editorial from Deeptech Journal 1996

Text by Richard Mannesto, photos by Terry Begnoche

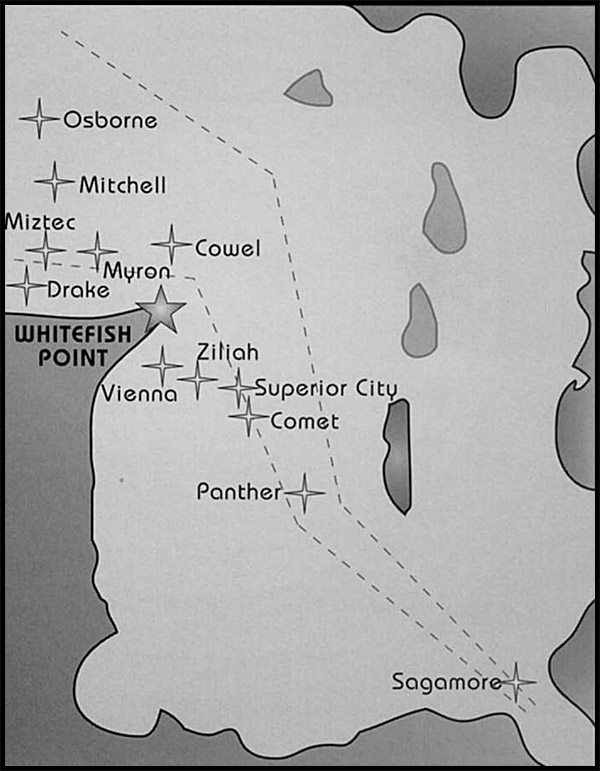

Lake Superior, also known as "Kirchigami" by the indigenous Indian population, is the largest of the Great Lakes as well as the widest and deepest. It is the only home of the Arikameg or Whitefish, a small Muller like fish that is typically smoked before eating. Whitefish Point, a peninsula on the Southeast side of Lake Superior near the point where Lake Huron connects to Lake Superior, is named for the large amounts of Arikameg found there. The large amounts of shipping traffic traveling between Lake Superior and Lake Huron combined with the often-severe storms common to this area have contributed to Whitefish Point becoming known as the ship graveyard of the Great Lakes. Whitefish Point, jutting our into the lake forms an obstacle that all vessels must successfully avoid.

Large-scale shipping was introduced to this area with the discovery of ore and other resources around the shores of Lake Superior in the early 1800s. With the completion of the Sr. Mary's Falls Canal, a series of locks and canals connecting Lake Superior and Lake Huron, shipping rapidly grew between the lakes.

Large ships, some 700-800 ft. long, traveling North or South around Whitefish Point must maneuver through relatively narrow shipping lanes in close quarters. With increasing demands on shipping in this area many shipwrecks in the Whitefish area have occurred due to collisions in the fog, blinding snow, and poor communications. Lake Superior is also known for the strength of the storms that blow here. Savage storms frequently pound Whitefish Point and are one of the major contributors to the dozens of large wrecks in the area. |

|

| |

|

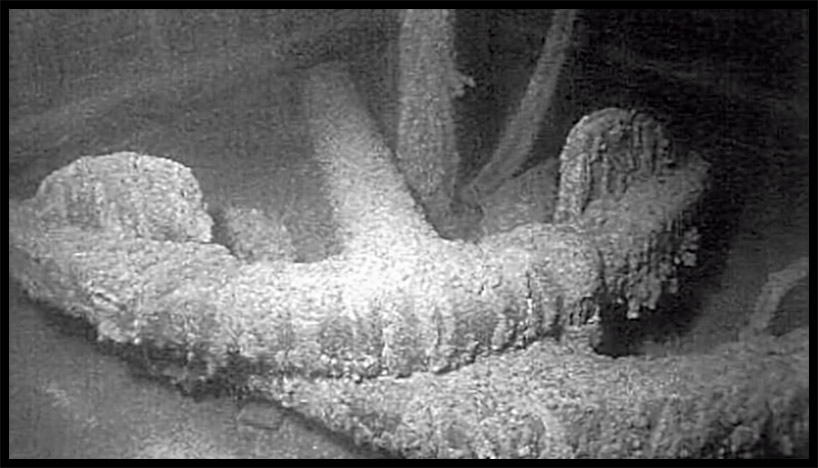

| The rudder and propeller on the Vienna are still in relatively good condition for having sunk in 1892. The near freezing water temperature preserves the ship from decay. |

|

|

|

| |

Ships that have sunk in Lake Superior are remarkably well preserved due to the cold (36° F) fresh water. Little decay occurs in the near freezing temperatures. Thermal protection for divers becomes as critical as gas supplies when diving these wrecks. An unprotected swimmer would last only a few minutes before hypothermia would set in.

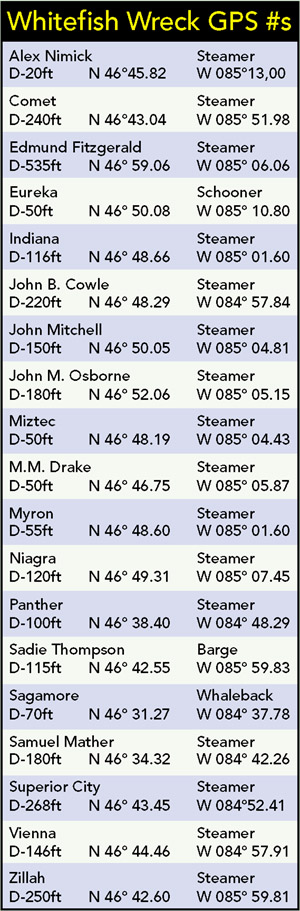

Depths for the wrecks of Whitefish Point vary with almost all of them below the 130 ft. limit for sport diving. Typical depths are in the 150-300 ft. range with some, like the Fitrzgerald much deeper (540 ft.). The cold-water temperatures combined with the depths limit diving this shipwreck holy-land to only highly experienced tech divers.

Local laws prevent the removal of artifacts from any of the wrecks in Lake Superior. These laws are enforced with heavy fines and a short stay at the local correctional facility. The shipwrecks of Whitefish Point represent a significant part of the history in this area and are protected by the local people and organizations like the Great Lakes. |

|

| |

|

| |

The Vienna 1873-1892

History-On September 16, 1892, the 191ft., 1,006 ton Vienna rounded Whitefish Point with the schooner Marcie C. Bell in row. The up bound steamer Nipigon approached with the schooners Melbourne and Delaware also in row. Both vessel operators issued port-to-port passing signals, but the 191-foot, 626 ton Nipigon veered at the last moment and smashed into the Vienna's port side. The lines to the Nipigon's schooners were quickly cut and the Nipigon attempted to drag the Vienna into shallow waters. The lines to the Vienna broke and she sank in 147 feet of water.

|

|

| |

|

| On the Vienna, a diver searches for artifacts below deck. Many artifacts from the Vienna hove been collected and are on display at the Great Lakes Shipwreck Museum. |

|

|

|

| |

Diving impressions-Located just a few miles south of Whitefish Point, the Vienna is one of the more popular wrecks because the site is protected from the strong northwesterly winds. The wreck sits upright and a permanent buoy is attached to the stern railing making. Most of the decking and the cabins were ripped free during the sinking. The large hole caused from the collision can be located on the port side forward’s the bow. The steam engine sits in place with the stack lying on its side on the deck. The mast and rigging has been snapped off and is scattered randomly on the deck. One of the original lifeboats later washed up on shore and was sunk onto the deck of the Vienna for divers to see. |

|

The Comet 1857-1875

History-On August 26, 1875 the 18 l ft., 621 ton Comet rounded Whitefish Point, carrying 70 tons of silver ore, 500 tons of pig iron, and a large shipment of wool. According to a survivor, Frances Dugot, the Captain of the Comet, spotted the Canadian steamer Manatoba just ahead. He then turned the Comet hard to port and gave a blast on the whistle. The Manatoba sliced deep into the bow ripping a fifteen-foot hole into the Comet. Reports from the crew and witnesses on the Manatoba stated that the Comet changed directions just before the ships passed bringing the Comet directly into the path of the Manatoba. Dugoc had apparently misjudged the direction of the Manatoba. After the collision, the Comet pulled free and swung around accidently smashing hard into the side of the Manatoba. The Comet quickly sank. The cabin structure separated from the deck as it disappeared below the surface. Six of the crew jumped to the Manatoba and another four were later rescued from the water. Six men were sleeping in the forecastle of the Comet and believed to be crushed by the impact. Another four crewmen were also lost in the dark waters. The cargo of unrefined silver ore distinguished the Comet as the only treasure ship sunk in Lake Superior. Kent Bellrichards located the wreck in the 70s. |

|

| |

|

| A diver examines the pig iron ingots located just forward of the steam engine on the deck of the Comet. |

|

|

|

| |

Diving Impressions-The Comet sits upright in 240ft. of water sunk deep into the mud bottom. The two wooden support arches, added to the Comet to increase structural strength, tower over the wreck. The steam engine, condenser, rudder, and prop arc still in good condition located on the stern section. Towards the center, the silver ore spills out into the mud where the Manatoba split the hull. The wool and pig iron bars are located just forward of the steam engine along with the smoke stack. The cabins were ripped off during the sinking and are scattered in the debris field around the wreck. The ship's name "Comet" is still visible on the condenser tank adjacent to the steam engine. |

|

| |

|

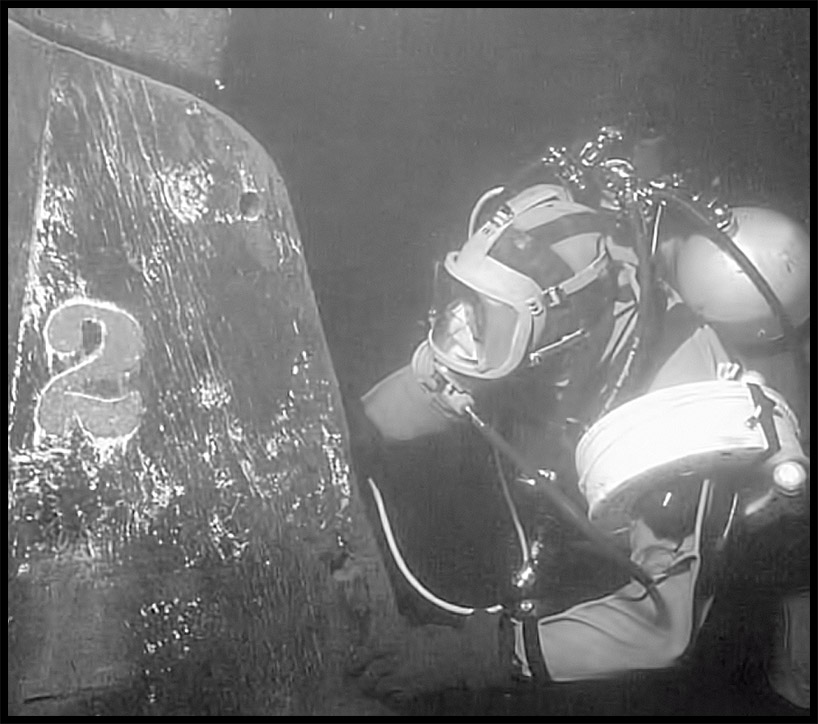

| A diver examines the rudder located at the stern end of the Comet. Many artifacts con be seen in the debris field which is spread around the stern. |

|

|

|

| |

John B. Cowel 1902-1909

History-On July 12, 1909, at 5:30 a.m. the 420 ft., 4,731 con John B. Cowel encountered a dense fog seventeen miles from Whitefish Point. The Issac M. Scott came unseen out of the fog and slammed into the port side of the Cowel. The Cowel, carrying 7,024 cons of iron ore, was quickly pulled down into the dark water. Fourteen crewmen perished on the wreck. A survivor recalled "When the ship sank, I was stuck in a whirlpool, wrenched and whirled until I thought my legs would be pulled off I saw a body along side me. lt was Will Thomas, my assistant. I tried to revive him when a broken hatch cover floated up and struck the lad, crushing his head. My life preserver came off and while I was floundering around in the water, another hatch cover came up. I grabbed the ring and pulled myself onto it. lt was three quarters of an hour before a lifeboat picked me up." The Cowel was discovered in 1972 in 220 feet of water, approximately two miles north of Whitefish Point.

|

|

| |

|

| Divers peer into the pilot house windows of the John B. Cowel in preparation for penelroting the wreck interior. |

|

|

|

| |

| Diving Impressions--The stern section is sitting upright and is tilted 15 degrees cowards amidships where the vessel split in half. The cabins are in good condition but access to the hull is limited due to the collapse of the ceilings during the sinking. A large stern anchor, life boar davits, capstan, and propeller are also in relatively good condition. The hatches to the cargo holds are missing, exposing the ore. Many artifacts like dishes, personal items, and rigging are scattered about the decks. |

|

| |

| |

|

| |

The Superior City 1898-1920

History-On August 20, 1920, the 429 ft., 4,795 ton Superior City, fully loaded with ore, was down bound in a heavy fog when the larger 580 foot steel steamer Willis L. King slammed into the Superior City's pore side. The crew of the Superior was on the deck attempting to lower the lifeboats when cold water flooded the boilers causing a large explosion that killed 28 crewmen. The explosion was so powerful it almost ripped the stern section from the ship. The wreckage was discovered by John Steele in 1972. |

|

| |

|

| The ships engine controls of the Superior City lay on their side inside the pilot house. Evidence of the tremendous explosion that sank the ship. |

|

|

|

| |

|

| The Superior City is remorkobly well preserved as shown by this photo of the pilot house interior. |

|

|

|

| |

Diving Impressions-- The Superior lies in 265 ft. of water with the stern section tilted up at a 45-degree angle. Dropping down over the stern you can see the name, propeller and rudder. A swim down the stern deck can be confusing due to the angle. Dishes and other artifacts are scattered about the stern section. The pilothouse is intact on the bow section. The wheel and compass were removed by the Great Lakes Shipwreck Society and can be seen today in the museum. Many artifacts are scattered around the pilot house along with personal belongings of the crew. |

|

John M. Osborn 1882-1884

History-On July 27, 1884 the 178 ft., 891 ton John M. Osborn left Marquette towing two schooner barges. Traveling in a thick fog, the crew periodically sounded the ships horn to warn other vessels of its approach. The answering blast of another horn came just seconds before the Alberta rammed the starboard side of the Osborn between the main and the mizzen masts. The vessels fortunately remained locked together long enough to enable most of the Osborn crew to climb aboard the Alberta. One of the courageous passengers on the Alberta climbed over to the sinking Osborn to help rescue the engine room crew. While he was below deck, the Osborn broke free of the Alberta, taking him and three Osborn crewmembers to the bottom. The Osborn was discovered in 1984 six miles north of Whitefish Point.

Diving Impressions-- The Osborn lies upright in 185 feet of water and is considered one of the best wreck dives at Whitefish Point, The ship is mostly Intact with the masts laying across the deck over the side. There are plenty of artifacts to see including rigging, dishes, and personal items. The collision area is easy to locate on the starboard side. The engine is interesting with tongue and groove wainscoting supporting it. The bow is in relatively good condition with the anchors lying on the deck. The holds are wide open and many artifacts can be seen such as block and tackle, dishes, and wheelbarrows. |

|

John M. Osborn 1882-1884

History-On July 27, 1884 the 178 ft., 891 ton John M. Osborn left Marquette towing two schooner barges. Traveling in a thick fog, the crew periodically sounded the ships horn to warn other vessels of its approach. The answering blast of another horn came just seconds before the Alberta rammed the starboard side of the Osborn between the main and the mizzen masts. The vessels fortunately remained locked together long enough to enable most of the Osborn crew to climb aboard the Alberta. One of the courageous passengers on the Alberta climbed over to the sinking Osborn to help rescue the engine room crew. While he was below deck, the Osborn broke free of the Alberta, taking him and three Osborn crewmembers to the bottom. The Osborn was discovered in 1984 six miles north of Whitefish Point.

|

|

| |

|

| The Oxborn's twin anchors are located on the deck, near the front bow section. |

|

|

|

| |

Diving Impressions-- The Osborn lies upright in 185 feet of water and is considered one of the best wreck dives at Whitefish Point, The ship is mostly Intact with the masts laying across the deck over the side. There are plenty of artifacts to see including rigging, dishes, and personal items. The collision area is easy to locate on the starboard side. The engine is interesting with tongue and groove wainscoting supporting it. The bow is in relatively good condition with the anchors lying on the deck. The holds are wide open and many artifacts can be seen such as block and tackle, dishes, and wheelbarrows. |

|

| |

|

| Many artifacts can be found below deck on the Osborn like this beverage container. |

|

|

|

| |

The Zillah 1890-1926

History-On August 20, 1926 The 202 ft., 1,1 00 ton Zillah encountered one of Lake Superior's fierce storms and unpredictable gale winds. With water crashing over the side and the Zillah taking on water, the captain tried to steer around Whitefish Point to gain protection from the high winds. Listing badly, the Zillah signaled for assistance from the Coast Guard. The Coast Guard managed to rescue all crew members bur the Zillah herself sank.

Diving impressions-The Zillah has not been dived as much as other wrecks due to the depth. However, this is changing with the increased popularity of mixed gas. lt sits upright in 252 ft. of water and the stern cabins were blown off when she sank. The boilers, engine and coalbunkers are in relatively good condition. The bow is intact but the wheel has been removed. Many artifacts such as block and tackle and hatch covers can still be seen lying about. |

|

Richard Mannesto holds a Masters Degree in Maritime History and Nautical Archaeology from East Carolina University and has been an active wreck explorer for 22 years. He is regarded as one of the most knowledgeable shipwreck archaeologists in the United States.

Special thanks to: Charlie Tulip, Billy Tulip, and Tom Farnquist.

Curt Bowen; founder and publisher of Deeptech Journal and Advanced Diver Magazine |

|

| |

|

| |