|

| |

|

|

|

|

ysteries surrounding the infamous shipwreck RMS Lusitania drift far beyond anyone’s imagination, including my own. As a deep wreck photographer, I joined a team of technical divers from the United Kingdom challenged with the task of probing just some of her secrets -- only to discover that the time for our explorations may indeed be running out! ysteries surrounding the infamous shipwreck RMS Lusitania drift far beyond anyone’s imagination, including my own. As a deep wreck photographer, I joined a team of technical divers from the United Kingdom challenged with the task of probing just some of her secrets -- only to discover that the time for our explorations may indeed be running out!

Lusitania is a name well known in the world of wreck diving, often referred to by the technical community as the "ultimate of all wreck dives." For decades historians have been baffled by the endless mysteries locked deep within the Celtic Sea. Today British technical divers have been working to unravel just some of them. Since the day the Lusitania sank, she has been shrouded in political controversy. Her story is one of conspiracy, greed, courtroom battles, ambition and obsession. Lusitania is a name well known in the world of wreck diving, often referred to by the technical community as the "ultimate of all wreck dives." For decades historians have been baffled by the endless mysteries locked deep within the Celtic Sea. Today British technical divers have been working to unravel just some of them. Since the day the Lusitania sank, she has been shrouded in political controversy. Her story is one of conspiracy, greed, courtroom battles, ambition and obsession.

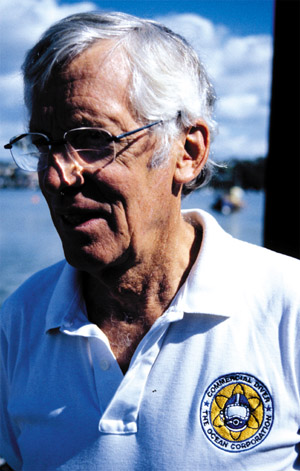

Since the summer of 1999, UK-based diver Mark Jones and his team have worked closely with the Lusitania's owner, Gregg Bemis of Sante Fe, New Mexico, in preparation for a forensic investigation of the ship's sinking, which is planned for 2003. In recent years tech divers have begun to reach depths historically reserved for commercial and military professionals supported by hundreds of thousands of pounds in equipment. Taking advantage of this fact, Bemis, who is 73, has utilized Jones’ team to extensively survey the present condition of the wreck with video and photographic evidence. But while Bemis' 2003 expedition will use elaborate and highly expensive saturation diving equipment usually associated with oil and gas exploration, Jones’ tech divers simply used closed circuit re-breathers alongside conventional scuba. In the case of Lusitania, the tech divers are operating at nearly 95m, this is between two and three times the depth attainable with mainstream scuba equipment. Since the summer of 1999, UK-based diver Mark Jones and his team have worked closely with the Lusitania's owner, Gregg Bemis of Sante Fe, New Mexico, in preparation for a forensic investigation of the ship's sinking, which is planned for 2003. In recent years tech divers have begun to reach depths historically reserved for commercial and military professionals supported by hundreds of thousands of pounds in equipment. Taking advantage of this fact, Bemis, who is 73, has utilized Jones’ team to extensively survey the present condition of the wreck with video and photographic evidence. But while Bemis' 2003 expedition will use elaborate and highly expensive saturation diving equipment usually associated with oil and gas exploration, Jones’ tech divers simply used closed circuit re-breathers alongside conventional scuba. In the case of Lusitania, the tech divers are operating at nearly 95m, this is between two and three times the depth attainable with mainstream scuba equipment.

|

|

|

|

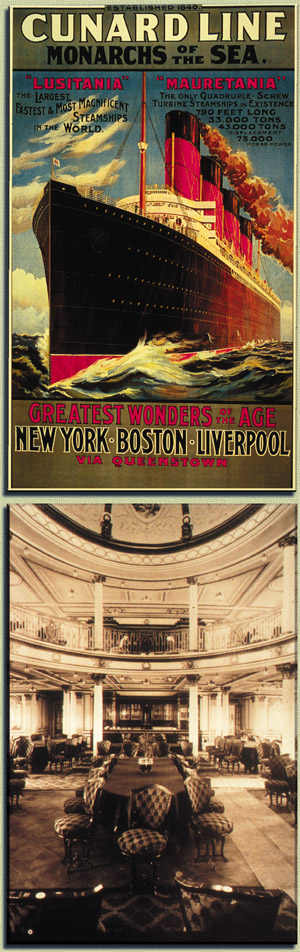

| Queen of the seas, Lusitania quickly became the very pride piece within the board game of international rivalry. |

|

|

|

|

With a terrific sense of excitement as to the wonders that lie below, my mind still concentrated upon a safe descent as I fell beneath the ocean’s surface. Whether using a revolutionary closed circuit or simply the plain, "old fashioned," traditional open circuit, the key tool that unites both and allows us to explore this type of wreck at such a depth is mixed gas. Dropping through my first gas switch depth at 98ft/30m, I began to breath a mixture of HeliAir 11/47 (11% O2 / 47% he ) concealed in my back-mounted, twin 20-litre cylinders. I had a lot to think about as I fell 305ft/93m into the Celtic Sea, even though I was descending down to the decks of one of the most famous shipwrecks in the world. The new gas mixture was designed to see me safely to the wreck; however, before I descended deeper a brief moment was spared to safely isolate that previous gas supply of nitrox which was vital for my return journey. Dropping deeper through the 30m thermo cline, unpredicted Atlantic tidal currents around the old head of Kinsale blessed me with only 5m of visibility. Still, the task at hand was to bring back as many images of the old liner that would best describe her present condition to the rest of the world. With a terrific sense of excitement as to the wonders that lie below, my mind still concentrated upon a safe descent as I fell beneath the ocean’s surface. Whether using a revolutionary closed circuit or simply the plain, "old fashioned," traditional open circuit, the key tool that unites both and allows us to explore this type of wreck at such a depth is mixed gas. Dropping through my first gas switch depth at 98ft/30m, I began to breath a mixture of HeliAir 11/47 (11% O2 / 47% he ) concealed in my back-mounted, twin 20-litre cylinders. I had a lot to think about as I fell 305ft/93m into the Celtic Sea, even though I was descending down to the decks of one of the most famous shipwrecks in the world. The new gas mixture was designed to see me safely to the wreck; however, before I descended deeper a brief moment was spared to safely isolate that previous gas supply of nitrox which was vital for my return journey. Dropping deeper through the 30m thermo cline, unpredicted Atlantic tidal currents around the old head of Kinsale blessed me with only 5m of visibility. Still, the task at hand was to bring back as many images of the old liner that would best describe her present condition to the rest of the world.

In 1995 a cultural preservation order was placed on the site designating Lusitania an historic shipwreck. Rumors that there could well be several old masters paintings among the wreckage concealed in lead tubes by the likes of Rubens & Monet were enough to convince Minister Higgins of its worthy status. If such paintings were recovered, they could well be of national importance as well as a controversial debate of to whom they would actually belong. As far as local government is concerned, the wreck lies in territorial waters and is therefore under the jurisdiction of DUCHAS, the national heritage service. In 1995 a cultural preservation order was placed on the site designating Lusitania an historic shipwreck. Rumors that there could well be several old masters paintings among the wreckage concealed in lead tubes by the likes of Rubens & Monet were enough to convince Minister Higgins of its worthy status. If such paintings were recovered, they could well be of national importance as well as a controversial debate of to whom they would actually belong. As far as local government is concerned, the wreck lies in territorial waters and is therefore under the jurisdiction of DUCHAS, the national heritage service.

The 'Lucy,' as she is often referred to, took her maiden voyage in 1907. Both she and her sister ship, Mauretania, would become hallmarked into history as the most luxurious liners of their day. On May 7, 1915, tragedy struck the Lusitania, securing the great ship a permanent place in 20th century maritime history -- a tragic shipwreck story that would become common household knowledge. While on a return journey from the United States, she was struck by a torpedo off the old head of Kinsale, fired from the German U-boat U-20. The Lusitania sank in only 18 minutes, resulting in the loss of 1,198 lives, a loss that would reverberate around the world. Along with the staggering death toll, a national treasure was lost. The 123 Americans lost aboard the ship eventually helped draw the United States into the Great War. The 'Lucy,' as she is often referred to, took her maiden voyage in 1907. Both she and her sister ship, Mauretania, would become hallmarked into history as the most luxurious liners of their day. On May 7, 1915, tragedy struck the Lusitania, securing the great ship a permanent place in 20th century maritime history -- a tragic shipwreck story that would become common household knowledge. While on a return journey from the United States, she was struck by a torpedo off the old head of Kinsale, fired from the German U-boat U-20. The Lusitania sank in only 18 minutes, resulting in the loss of 1,198 lives, a loss that would reverberate around the world. Along with the staggering death toll, a national treasure was lost. The 123 Americans lost aboard the ship eventually helped draw the United States into the Great War.

As the Lusitania slipped beneath the waves, she took with her many mysteries -- although one such mystery has singled itself out from the rest, baffling maritime historians for decades. Shortly after the U-20s torpedo slammed into her starboard bow, she was rocked by another mysterious explosion, an explosion that was large enough to send her down. In theory the Lusitania was too big to be sunk by a single torpedo. Historians have speculated as to what she was carrying that would result in such an explosion. Conspiracy theorists claim the most provocative in that that she was carrying an illegal cache of ammunition for delivery from America to the allies. Others put claim to a coal dust explosion or even a sudden release of steam pressure. While there is frequent disagreement over the source of the secondary explosion, there is one point that those familiar with the ship agree on: Lusitania's wreck may be hiding an answer to one of history's most fascinating mysteries. It is a mystery Bemis is determined to solve. As the Lusitania slipped beneath the waves, she took with her many mysteries -- although one such mystery has singled itself out from the rest, baffling maritime historians for decades. Shortly after the U-20s torpedo slammed into her starboard bow, she was rocked by another mysterious explosion, an explosion that was large enough to send her down. In theory the Lusitania was too big to be sunk by a single torpedo. Historians have speculated as to what she was carrying that would result in such an explosion. Conspiracy theorists claim the most provocative in that that she was carrying an illegal cache of ammunition for delivery from America to the allies. Others put claim to a coal dust explosion or even a sudden release of steam pressure. While there is frequent disagreement over the source of the secondary explosion, there is one point that those familiar with the ship agree on: Lusitania's wreck may be hiding an answer to one of history's most fascinating mysteries. It is a mystery Bemis is determined to solve.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Left: In the wake of inhuman outrage, Lusitania’s dead are buried in mass graves.

Below: Kapitanleutnant Walther Schwieger, the man who sank the Lusitania from the German U-Boat, U-20.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Lying at 305ft/93m the wreck was deep, big and complicated, due to the considerable collapse throughout the ship. As darkness descended upon us, my partner, Chris Hutchison, and I fired up 200 watts of light between us and within the next few minutes our eyes adjusted and we were ready to begin exploring. It is true to say that taking into consideration the shattered state of the wreck, it's possible to count on one hand individuals that positively know their way around the entire site. With an obvious amount of navigational artifacts in the area, we considered our first drop positive for what was to become the start of a planned video survey of the wreck. If all went well our goal was to run a guide line from the bow to the very stern, then at strategic points run branch lines off at pre-determined positions in order for designated teams to search and film. In all we hoped to have an end result of the first true video mosaic of the entire wreck -- footage that historians could use to resolve unanswered questions. DUCHAS, on the other hand, each day monitored the operations, and as events unfolded, a nearby Navy frigate watched over our site activities. The wreck work was taken quite seriously and imposed legislation had even prevented Bemis himself from undertaking controlled work over what in theory is his own property. Lying at 305ft/93m the wreck was deep, big and complicated, due to the considerable collapse throughout the ship. As darkness descended upon us, my partner, Chris Hutchison, and I fired up 200 watts of light between us and within the next few minutes our eyes adjusted and we were ready to begin exploring. It is true to say that taking into consideration the shattered state of the wreck, it's possible to count on one hand individuals that positively know their way around the entire site. With an obvious amount of navigational artifacts in the area, we considered our first drop positive for what was to become the start of a planned video survey of the wreck. If all went well our goal was to run a guide line from the bow to the very stern, then at strategic points run branch lines off at pre-determined positions in order for designated teams to search and film. In all we hoped to have an end result of the first true video mosaic of the entire wreck -- footage that historians could use to resolve unanswered questions. DUCHAS, on the other hand, each day monitored the operations, and as events unfolded, a nearby Navy frigate watched over our site activities. The wreck work was taken quite seriously and imposed legislation had even prevented Bemis himself from undertaking controlled work over what in theory is his own property. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

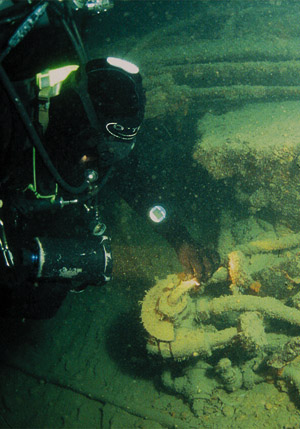

Photo: British wreck diver, Bob Hughes puts scale to the docking bridge telegraphs. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

The wreck lies on its starboard side at an angle of approximately 30 degrees, with the keel taking an unusual curvature, one that is not of obvious construction. Much of the superstructure was gone, thus taking with it integral strength which may give reason as to the hull’s slumping appearance. The beam in this location had collapsed from its original 27m to approximately half of that and all of the funnels were missing, presumably due to deterioration. The bow location of the wreck was by far the most prominent section of the wreck. It remains intact and shipshape which, in turn, makes navigation simple in respect. Swimming aft of where the bridge would have been, the wreck then becomes seriously complicated, from here on with little visibility veteran divers of the wreck may benefit, but newcomers will simply become lost. The wreck lies on its starboard side at an angle of approximately 30 degrees, with the keel taking an unusual curvature, one that is not of obvious construction. Much of the superstructure was gone, thus taking with it integral strength which may give reason as to the hull’s slumping appearance. The beam in this location had collapsed from its original 27m to approximately half of that and all of the funnels were missing, presumably due to deterioration. The bow location of the wreck was by far the most prominent section of the wreck. It remains intact and shipshape which, in turn, makes navigation simple in respect. Swimming aft of where the bridge would have been, the wreck then becomes seriously complicated, from here on with little visibility veteran divers of the wreck may benefit, but newcomers will simply become lost.

As this was the first dive of our third expedition with no positive destination as such, we moved off in a direction toward the stern. Our first location was an area of covered mosaic-tile flooring found in the vestibule and located in first class where passengers entered from the boat deck. Further along and immediately beyond the first funnel void were three main fresh water tanks still housed in their original location -- the working valves appeared readily recognizable. My attention was now distracted by the beckoning flash of Hutch's torch and on reaction I discovered he had found a rare example of a tropical porthole. Lying free from its fixing, a small amount of netting drifts on before we took time to photograph this rare artifact. As this was the first dive of our third expedition with no positive destination as such, we moved off in a direction toward the stern. Our first location was an area of covered mosaic-tile flooring found in the vestibule and located in first class where passengers entered from the boat deck. Further along and immediately beyond the first funnel void were three main fresh water tanks still housed in their original location -- the working valves appeared readily recognizable. My attention was now distracted by the beckoning flash of Hutch's torch and on reaction I discovered he had found a rare example of a tropical porthole. Lying free from its fixing, a small amount of netting drifts on before we took time to photograph this rare artifact.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Above: After numerous years of courtroom battle and expense, Gregg Bemis now officially puts claim to Lusitania’s outright ownership.

|

|

Below: Expedition leader Mark Jones looks on at the remains of a window and electrical light fitting that once embraced the covered promenade deck. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

After a period of severe weather, our team returned to the wreck. However, over the next period of dives, we concentrated on the stern section of the wreck. This is where I saw more damage than elsewhere around the site. During the summer of 1982, the giant salvage company, Oceaneering, recovered three of Lusitania's four props by blasting. Accompanied by extensive depth charging during World War II, the damage soon became explanatory upon my dives. The Lusitania’s once proud counter stern was no longer apparent, while the entire docking bridge now rests over the starboard seabed among a huge debris field. Here, within twisted sections of the superstructure, lies her docking telegraphs alongside the main docking bridge telemotor. Elsewhere, as I made my way through the debris field, numerous types of windows were seen -- many displaying ornate filigreed that detailed the very affluent standards of the early twentieth century. The main bridge itself had also collapsed down to the seabed, and it is here that I found even more intricate, turn-of-the-century navigational equipment. Moving on, a first class bath tub lies aft, still immaculately intact complete with its original brass shower framework. A few meters away, I saw the Lusitania's beautiful tripe chime whistle. After a period of severe weather, our team returned to the wreck. However, over the next period of dives, we concentrated on the stern section of the wreck. This is where I saw more damage than elsewhere around the site. During the summer of 1982, the giant salvage company, Oceaneering, recovered three of Lusitania's four props by blasting. Accompanied by extensive depth charging during World War II, the damage soon became explanatory upon my dives. The Lusitania’s once proud counter stern was no longer apparent, while the entire docking bridge now rests over the starboard seabed among a huge debris field. Here, within twisted sections of the superstructure, lies her docking telegraphs alongside the main docking bridge telemotor. Elsewhere, as I made my way through the debris field, numerous types of windows were seen -- many displaying ornate filigreed that detailed the very affluent standards of the early twentieth century. The main bridge itself had also collapsed down to the seabed, and it is here that I found even more intricate, turn-of-the-century navigational equipment. Moving on, a first class bath tub lies aft, still immaculately intact complete with its original brass shower framework. A few meters away, I saw the Lusitania's beautiful tripe chime whistle.

Each year the dive team has been based at the nearby town of Kinsale, although the 2001 expedition was based from Baltimore, which makes for a boat journey of some two hours out to the wreck. John Kearney's Baltimore dive center was more than adequate to deal with the huge turnover of gas filling each day. A fixed Rota determined when each video team dove to the wreck and which days they stayed ashore to mix the following day’s gas supply. The gas supply of Helium and Oxygen was shipped in "Quad packs," then craned into position. A system of partial pressure blending is then undertaken to transfer the gas to the diving cylinders. As the gas levels lower, they are then boosted by the aid of a Haskel pump which effectively sucks the remaining low pressure gas from the Quads, boosting them into the diving cylinders. With 50 percent of the team using closed circuit re-breathers, the gas filling process took considerably less time which, in turn, meant there was more time for team meetings and further discussions of the day's events. Each year the dive team has been based at the nearby town of Kinsale, although the 2001 expedition was based from Baltimore, which makes for a boat journey of some two hours out to the wreck. John Kearney's Baltimore dive center was more than adequate to deal with the huge turnover of gas filling each day. A fixed Rota determined when each video team dove to the wreck and which days they stayed ashore to mix the following day’s gas supply. The gas supply of Helium and Oxygen was shipped in "Quad packs," then craned into position. A system of partial pressure blending is then undertaken to transfer the gas to the diving cylinders. As the gas levels lower, they are then boosted by the aid of a Haskel pump which effectively sucks the remaining low pressure gas from the Quads, boosting them into the diving cylinders. With 50 percent of the team using closed circuit re-breathers, the gas filling process took considerably less time which, in turn, meant there was more time for team meetings and further discussions of the day's events.

Despite the fact that the archaeology community has repeatedly defined archeologically interesting wrecks to be those over 100 years old, they nevertheless seem unable stay away from Lusitania, a wreck that sank only 86 years ago. This community has also in general been fiercely opposed to the raising of artifacts from shipwrecks by anyone except archaeologists, arguing that only they are capable of understanding the full significance of the unique arrangement of these artifacts on the seabed. Some archaeologists even object to there own kind raising artifacts because "that would be destroying the unique arrangement for future generations of who may also wish to carry out their own excavations and studies." Despite the fact that the archaeology community has repeatedly defined archeologically interesting wrecks to be those over 100 years old, they nevertheless seem unable stay away from Lusitania, a wreck that sank only 86 years ago. This community has also in general been fiercely opposed to the raising of artifacts from shipwrecks by anyone except archaeologists, arguing that only they are capable of understanding the full significance of the unique arrangement of these artifacts on the seabed. Some archaeologists even object to there own kind raising artifacts because "that would be destroying the unique arrangement for future generations of who may also wish to carry out their own excavations and studies."

A factor in this difficult debate that often does not seem to be taken into account is that the bottom of the sea is not a benign environment where a shipwreck's remains will stay perfectly preserved forever. This is especially true with the Lusitania; the exposed position of the wreck makes her particularly vulnerable to the often-strong Atlantic under currents and swells. Added to this are the highly corrosive forces of nature and the almost acid bath of seawater itself. The scouring action of currents and sand movements and the pounding of wreckage/artifacts against rocks/wreckage are clearly perils for wrecks in shallow water. But even wrecks in deep water, such as the Lusitania, are subject to slow destruction through the activity of bacteria eating away the ferrous metal of the hull, thus creating deposits of rusticles. For deep shipwrecks of this vintage, rusticles remain the main enemy in removing .1 of a ton of iron from the steel construction everyday; therefore, the estimate would suggest a time matter of possibly 90 years until the wreck biologically implodes, collapses into itself and simply becomes an iron ore deposit on the floor of the ocean. A factor in this difficult debate that often does not seem to be taken into account is that the bottom of the sea is not a benign environment where a shipwreck's remains will stay perfectly preserved forever. This is especially true with the Lusitania; the exposed position of the wreck makes her particularly vulnerable to the often-strong Atlantic under currents and swells. Added to this are the highly corrosive forces of nature and the almost acid bath of seawater itself. The scouring action of currents and sand movements and the pounding of wreckage/artifacts against rocks/wreckage are clearly perils for wrecks in shallow water. But even wrecks in deep water, such as the Lusitania, are subject to slow destruction through the activity of bacteria eating away the ferrous metal of the hull, thus creating deposits of rusticles. For deep shipwrecks of this vintage, rusticles remain the main enemy in removing .1 of a ton of iron from the steel construction everyday; therefore, the estimate would suggest a time matter of possibly 90 years until the wreck biologically implodes, collapses into itself and simply becomes an iron ore deposit on the floor of the ocean.

The Lusitania's hull was indeed in poor condition and appears to be folded in on itself, whether this was due to collapsed deck levels with no internal strength or simply previous salvage attempts, I do not know. Just how much strength the hull plating has in order to remain in its present condition may be determined through forensic analysis. The strength of the rivets naturally will determine the life of the present hull configuration, thus an analysis of rivets of a specific collective trend could quite possibly determine a given life span. A cross sectional analysis of rivets to measure the quantity of slag will give an indication as to whether the original construction contained the optimum quantity within the wrought iron. Through an analysis of this nature, it may be possible to estimate the wreck’s time span from its present state. The wreck lies along a bearing of almost 230 degrees southwest to northeast, and it is in a position of fast currents that will not help to preserve her condition in any form. The Lusitania's hull was indeed in poor condition and appears to be folded in on itself, whether this was due to collapsed deck levels with no internal strength or simply previous salvage attempts, I do not know. Just how much strength the hull plating has in order to remain in its present condition may be determined through forensic analysis. The strength of the rivets naturally will determine the life of the present hull configuration, thus an analysis of rivets of a specific collective trend could quite possibly determine a given life span. A cross sectional analysis of rivets to measure the quantity of slag will give an indication as to whether the original construction contained the optimum quantity within the wrought iron. Through an analysis of this nature, it may be possible to estimate the wreck’s time span from its present state. The wreck lies along a bearing of almost 230 degrees southwest to northeast, and it is in a position of fast currents that will not help to preserve her condition in any form.

On no occasion did any member of the team witness any such artifacts within the wreckage that may be recognized as those of national treasures. It is possibly quite important to encourage that fittings and fixtures of Lusitania, including navigational equipment, be viewed as such treasures for future generations and most certainly should be used for some form of preserved educational purpose. As it stands the heritage service will not grant a license for the recovery of artifacts unless they are done so within the parameters of an archaeological pattern. While DUCHAS does not have the means to carry out this kind of work, time and time again the subject results in the question of funding. Indeed if this site has become a national site of interest, then I believe it should undoubtedly be treated as such. The Lusitania is one of the first wrecks less than 100 years old to have such a preservation act placed upon it. Since this is the case, then I believe she surely should also become one of the first wrecks to have her artifacts preserved before it is too late. On no occasion did any member of the team witness any such artifacts within the wreckage that may be recognized as those of national treasures. It is possibly quite important to encourage that fittings and fixtures of Lusitania, including navigational equipment, be viewed as such treasures for future generations and most certainly should be used for some form of preserved educational purpose. As it stands the heritage service will not grant a license for the recovery of artifacts unless they are done so within the parameters of an archaeological pattern. While DUCHAS does not have the means to carry out this kind of work, time and time again the subject results in the question of funding. Indeed if this site has become a national site of interest, then I believe it should undoubtedly be treated as such. The Lusitania is one of the first wrecks less than 100 years old to have such a preservation act placed upon it. Since this is the case, then I believe she surely should also become one of the first wrecks to have her artifacts preserved before it is too late.

E-mail: leigh@deepimage.co.uk

http://www.deepimage.co.uk/

|

|

|

|

|

| Above: Deep inside Lusitania’s holds, divers find all manner of machinery and cargo still lashed into position. |

|

|

|

|

|

| Above: Huge chain links on the bow of the wreck can be seen running into their foredeck hawsers. |

|

|

|

|

|

| Above: The stern docking telemotor that once hydraulically steered Lusitania into harbour. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|